A New Peruvian Route to the Plain of the Amazon

By Solon I. Bailey*

Associate Professor of Astronomy, Harvard College Observatory

A commercial conquest of the heart of the South American continent is going rapidly forward. While the coast regions have been settled and civilized for centuries, colonization has hardly touched the great plains of the upper Amazon and the lower valleys of the eastern Andes. Only Yesterday, indeed, this vast region was almost unknown; today little remain which has not been at least partially explored. Nor is it now any thought of the millions who in the future may here make their homes which is working for the development of the country but simply the desire to be first in the exploitation of its natural wealth, especially rubber.

Commerce naturally follows the lines of great rivers, and nowhere else are there such vast water systems as in South America: nor does it seem improbable that the same law will hold true here, especially alter the possibilities of the tributaries of the Amazon have been properly developed, and that the commerce of southeastern Peru and Bolivia will find its way to the Atlantic, thousands of miles distant, rather than to the Pacific, only a few hundred miles away. This has been true in the past, and is. strikingly illustrated by Iquitos. in northeastern Peru, which is practically an Atlantic seaport, although in Peruvian territory and 2,000 miles from the mouth of the Amazon. From southeastern Peru and Bolivia. however, in the regions of the Madre de Dios and the Beni. communication with the Atlantic is more difficult. This is due especially to the falls of the Madeira, near the junction of the two rivers named above. These rapids block navigation at a distance of 2,000 miles from the mouth of the Madeira. Above the falls steamships may again be used; but the danger and loss in passing the rapids are so great that, until this difficulty is overcome, another route is very desirable. The Pacific is comparatively near, but a journey must be made through dense forests and wild gorges to the crest of the eastern Andes and down to the Titicaca Plateau, where railway transportation to the Pacific is ready. Until recently no direct route had been opened up.

At the present time there are several ways of reaching the Madre de Dios and its tributaries, but the most direct and comfortable route is that which I traversed in 1903 before its completion. Since that time many improvements in the road have been made.

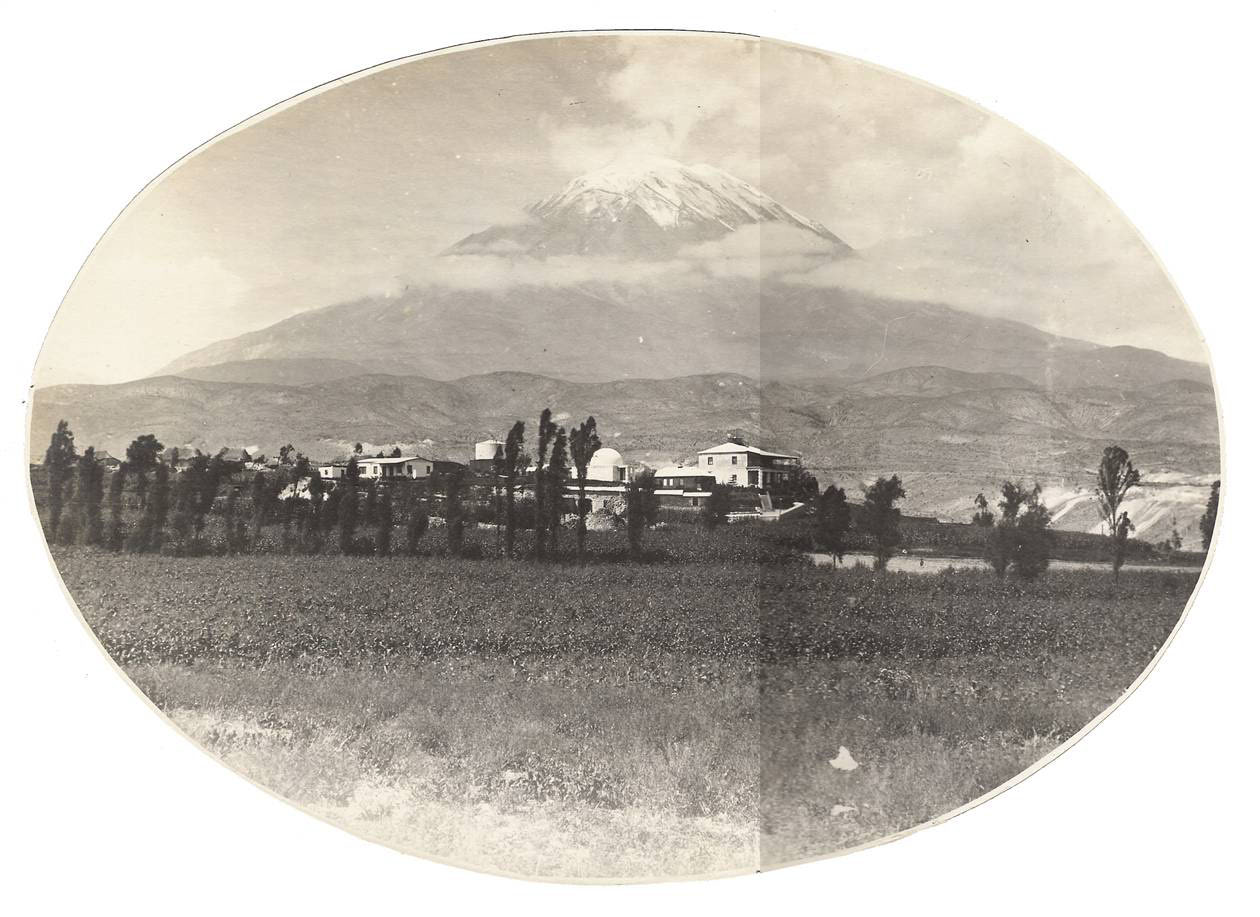

From New York one may reach the Peruvian port of Mollendo in about three weeks. At the present time it is necessary to cross the Isthmus of Panama by rail, but when the canal is completed through steamships from Atlantic cities will doubtless call at all important South American Pacific ports. From Mollendo a railway journey of seven or eight hours takes one across the desert to Arequipa, the chief city of southern Peru. Arequipa lies on the western slope of the Andes, at an elevation of 7,500 feet. This elevation within the tropics furnishes an almost ideal climate. The whole region west of the Andes in Peru is, however, desert and capable of cultivation only by irrigation. Arequipa owes its existence to the small River Chile, whose waters are exhausted in irrigating the valley which surrounds the city.

A railway leads from Arequipa to the Titicaca Plateau, which lies between the eastern and western Andes. On the lofty and desolate Puna it reaches an altitude of 14,660 feet before it descends to the plateau. Lake Titicaca has an elevation of about 12,500 feet. This great region between the different ranges of the Andes was the home of the various Indian races that under the domination of the Incas made up the semi-civilized population at the time of the Spanish conquest. Their descendants, for the most part full-blooded Indians, still dwell on the same plateaus and lofty valleys, but in a low social condition. They have lost rather than gained by the coming of a higher civilization.

Crossing the Andes

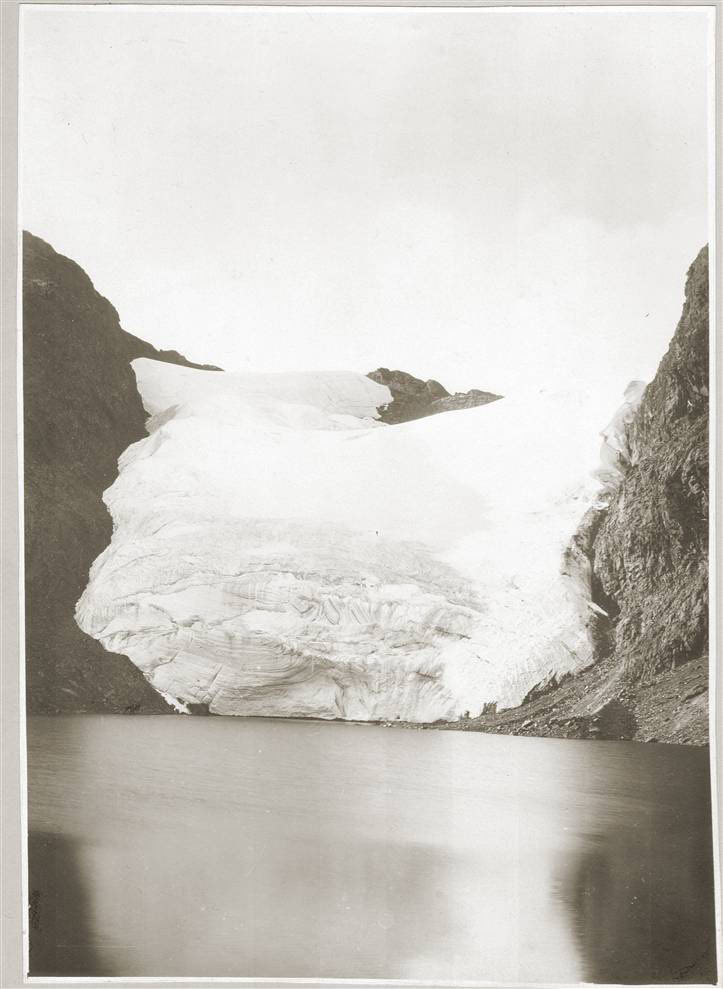

At Tiripata, on this plateau, it is necessary to leave the railway and cross the eastern Cordillera. Through American enterprise, in connection with an enlightened policy on the part of the Peruvian government, a wagon road has been constructed for a portion of the route across the plateau, and will be carried over the mountains to a small Indian town on the eastern slope. From this town a good trail for miles will be built, down to some navigable river on which small steamers can be used. With the railway most of the comforts of civilization are left behind. In four or five days of mule-back travel we mount the eastern Andes, winding our way through the Aricoma Pass at an altitude of about 16,500 feet. Here the scenery, if the weather is fine, repays the hardships of the trip. Snowy mountains and enormous glaciers are mirrored in the waters of lakes, which change their colors with every whim of cloud and sky. More often, however, the traveler is wrapt in blinding snowstorms, which shut out every glimpse beyond the narrow limits of a few feet. Hour after hour he clings half frozen to his mule, his discomfort heightened by the mountain sickness, which is one of the terrors of these lofty regions. To lose his way under these conditions may mean death.

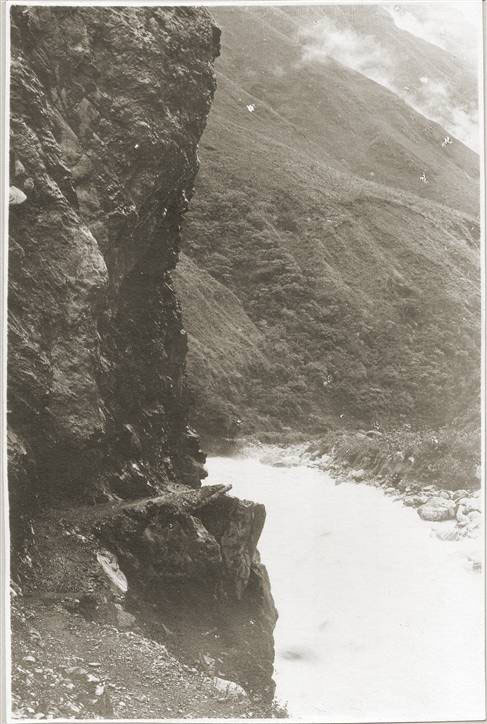

On reaching the eastern crest of these mountains, if the view is clear, one seems to be standing on the edge of the world. The eye, indeed, can reach but little of the vast panorama, but just at one's feet the earth drops away into apparently endless and almost bottomless valleys. We may call them valleys, but this does not express the idea; they are gorges, deep ravines in whose gloomy depths rage the torrents which fall from the snowy summits of the Andes down toward the plain. We might hunt the world over for a better example of the power of running water. The whole country is on edge. Here all the moisture from the wet air, borne by the trade winds across Brazil from the distant Atlantic, is wrung by the mountain barrier and falls in almost continual rain.

Near the summit of the pass only the lowest and scantiest forms of vegetable life are seen. In a single day, however, even by the slow march of weary mules, in many places literally stepping "downstairs" from stone to stone, we drop 7,000 feet. Here the forest begins, first in stunted growths, and then, a little lower down, in all the wild luxuriance of the tropics, where moisture never fails. The lower eastern foothills of the Andes are more heavily watered and more densely overgrown than the great plain farther down. Here is a land drenched in rain and reeking with mists, where the bright sun is a surprise and a joy in spite of his heat. In these dense forests, with their twisting vines and hanging lianas, a man without a path can force his way with difficulty a mile a day.

In these foothills, at an elevation of 4,000 or 5,000 feet, is the Santo Domingo mine. Here is an American colony provided with comfortable, almost luxurious, dwellings, which are flanked by the unsightly huts of native miners and Indians.

From this abode of comparative luxury we again started mule-back along a new but splendid trail down into the "rubber country." Four days of this travel, through forests peopled with nothing more frightful than jaguars and monkeys, brought us to the end of the trail. Day after day ten hours a day in the saddle is sufficiently tiresome, but it was with regret that we left our animals to try the forest afoot. Our first experience involved only a walk of a couple of hours, but over a trail so narrow, steep, and blocked with trees and roots that we were soon exhausted. We were glad enough to arrive at a clearing on the bank of a recently discovered stream called the New River. After a delay of a day or two at this post, we made our way down stream a few miles to the junction of the New River with the Tavora, on whose waters we intended to embark. Six hours of walking over a path known in the picturesque language of my companions as "A hell of a trail" brought us to the junction, where we found another camp with a group of workmen of various nationalities.

Through an Unknown Country

The party which I joined for the trip down the rivers was under the direction of Mr. Chester Brown, the general manager of the Inca Rubber Company. To him and to his genial brother "Fred" I am indebted for some of the most interesting experiences which the present day furnishes. The route we took to the Madre de Dios had been traversed but once previously by a white man, and then only a few weeks before by an engineer in the employ of the company. At the place where we embarked on the River Tavora we were still well up among the foothills of the Andes, and navigation, even in canoes and rafts, was attended by many difficulties and some dangers, owing to the numerous rapids.

The canoes are dugouts shaped from a single log. They are from twenty to twenty-five feet long, two or three feet broad, and readily carry half a dozen men and several hundred pounds of freight. For the passage upstream only canoes are used, and they are propelled by paddles or by poles, according to the depth and swiftness of the water. For the journey down the river, however, rafts are also used, since the rapid current renders great exertion unnecessary. Many of the native woods are too heavy for rafts; indeed, a number of varieties sink at once, so great is their specific gravity. The variety used for rafts is nearly as light as cork. A number of logs of this raft-wood are fastened together by driving through them long wood pins, made of a kind of palm which is so hard that it takes the place of iron. Crosspieces are then fastened on in the same way, and the front end is made pointed, so that the craft shall not be stopped by collision with driftwood or boulders. When finished the raft consists entirely of wood, and no tool has been used in its construction except an axe.

With two rafts and two canoes, our party set out one day about noon. The trip began with the running of a swift rapid, which was one of many to follow. The canoes generally led the way and pointed out the best route. In many cases there were sharp curves, with here and there the stranded trunks of great trees and huge boulders. Many of our experiences were sufficiently exciting, and a fall into the river was a common incident of the trip. Our company included a crew of ten men, a motley crowd of various colors and nationalities. A nearly continuous stream of profanity attended the various maneuvers of our fleet, which reached its climax in intensity and picturesqueness when some sudden jar projected one or more of the boatmen into the water. At such times familiarity with the language of the boatmen would have been a misfortune. In the swifter and shallower rapids of the upper streams it was often necessary to lighten the load by wading in the water beside the canoes, which were guided by hand or even by a rope carried along the bank. This sort of travel, together with frequent rains, caused all the party to be soaked with water from morning to night, and we were fortunate when the kits, were kept dry, so that the night could be passed in comfort. At one time during the expedition rain fell in prodigious quantities, causing the river to rise nearly ten feet within twenty-four hours. Progress became difficult and extremely dangerous, owing to the swiftness of the current and the trunks of trees carried along on its surface. We were obliged to make camp and wait. This we did at a place which seemed sufficiently elevated above the surface of the river. The following night, however, the water reached our camping ground and compelled us to change quarters in the darkness. Pitching a new camp at midnight, in a tropical jungle, in a pouring rain, is a far from cheerful occupation. The Tavora, a river found on no map yet published, is one of the branches of the Tambopata, a stately stream but little known. The Tambopata is a tributary of the Madre de Dios, which joins its waters with those of the Beni and other rivers to form the Madeira. The Madeira is one of the great rivers of the world, and yet it is only one of the sources of the mighty Amazon.

Until our embarkation we had been continually in deep, densely wooded valleys, our view always shut in by their lofty sides. On the second day down the Tavora, however, as we swept out into the broader waters of the Tambopata, the hills fell away suddenly, leaving before us only the level Amazonian plain--one vast forest, extending unbroken, save for the river courses, for hundreds, even thousands, of miles. At rare intervals the banks rise in bluffs fifty or a hundred feet above the general level, but usually it is an unbroken, forest-covered plain, rising only a few feet above the level of the river, and in time of flood covered for great distances by the swollen waters. It is a forest, so far as I saw, without a single natural opening or glade, except along the banks of the rivers. For days we had longed to see the hills melt away and the plain appear; a month later, while working our slow way up the river, we watched with even greater eagerness to catch again a glimpse of the blue hills outlined against the sky.

The Chunchos

In the shade of this ever-present forest live various groups of savages, known as Chunchos. They dwell in general along the banks of the rivers, and indeed they seem almost as much at home on, or even in, the river as on the land. The reputation which they enjoy is none of the best. We met half a dozen groups during our expedition, some of whom apparently had never before seen white men. They impressed me as simple and well-disposed, if treated fairly, and surprisingly intelligent. Indeed, several times while attempting to converse with them by means of signs I could not resist the impression that they were merely masquerading under the guise of savagery. From almost every standpoint, however, they are mere savages. They are nomadic, roaming up and down the rivers and building only the rudest huts. They have no metal implements, so far as I could learn, and few, if any, made of stone. Some of them appear to have no proper household utensils. and such scant pottery as I saw was very rude. Their clothing is made of the fibrous bark of a certain tree, called by them Ianchama. This is stripped off in large pieces and pounded on flat stones with great patience until the coarser materials are removed and only the inner, tough, but rather soft and pliable, bark is left. This resembles in texture a coarse cloth. Two pieces of this material are sewed together to form a sleeveless shirt which reaches from the shoulders to the knees. Shawls and loincloths are also made from the same bark. These garments are not always worn, however, for when we approached a village unannounced both men and women completely nude were sometimes seen.

Their ideas in regard to propriety were satisfied by a loincloth, and several young women of modest mien and rather dignified presence stood and attempted to talk with us dressed in this fashion. Another girl, without the slightest suspicion in her manner of any impropriety in the act, removed the shirt she was wearing in order to exchange it for one made of cloth offered, to her by a member of our party. The Garden of Eden still lingers here. These Amazonian Eves have evidently never heard of The Fall. Like other people, however, they take pride in dress. Jewelry also is worn, made of the teeth of monkeys or of pretty shells. Nose ornaments are worn, which no doubt add some charm for Chuncho eyes, but which are decidedly inconvenient when eating.

Insects are a great pest, even to these hardy children of the forest, who slip into the water frequently to be free from their stings and to cool themselves. Men and women, boys and girls, threw themselves into the water, unmindful of our presence, and swam about in unencumbered grace.

Food is abundant with them--plantains and yuccas, as well as game and fish. The weapons of war and those of the chase are much alike, consisting of bows, spears, and arrows, all made of an extremely hard variety of palm. With these they wage war on unfriendly neighboring tribes, and also hunt the tapir, deer, monkeys, wild turkeys, and fish. They roast the flesh of animals and fish, either by placing it directly in the fire or first inclosing it in hollow pieces of cane or bamboo. The heads of monkeys and of the larger kinds of fish seem to be regarded as dainties, and are simply placed in the fire and roasted or burned to the proper point. Monkey meat, when properly cooked, is palatable enough; but the appearance and manner of a large monkey is so human that when roasted and served whole it gives a cannibal air to the meat somewhat disagreeable to me. No such thought, however, comes to the Chuncho.

They have a curious combination of rather bright and ''taking" ways and of low and filthy habits. Their continual bathing renders them free from personal unpleasantness, though it is doubtful if they enter the water with any idea of cleanliness. Their sense of humor is as quick as that of an Irish man. With no idea of our language, they seemed to catch a joke at once and were frequently laughing. This is in great contrast with the Indians of the Peruvian Plateau, who are slow in thought and movement and seldom laugh, at least in the presence of strangers. Many of the Chunchos whom we met apparently saw white men for the first time. Certainly no one of them had ever seen a bald man; One of our party was decidedly bald, and when he removed his hat a look of surprise and amusement passed over the faces of the whole group, accompanied by sly, if expressive, remarks. Freedom from the use of hats may account for the absence of baldness among them. It is an interesting fact, however, that among the different groups which we met, no person, man or woman, appeared to me over forty years of age. What became of the aged I could not learn.

I have never seen a more interesting affair than a luncheon which a party of Chunchos took with us on our way down the Tambopata. Our limited stores of provisions contained marvelous novelties for them. Sugar was quite unknown to them. Each took some in the palm of his hand and tasted it slowly and cautiously; then a smile of satisfaction lighted up his face, and the sugar disappeared. Men and women, impelled by curiosity, mingled freely and frankly among us, and although among themselves the women are probably accustomed to eat after the men, with us they all came together in apparent equality. For pickles they expressed great disgust. Tea was taken with indifference or contempt, but cocoa with plenty of sugar pleased them extremely. A little confectionery, in the form of rather solid balls, was eaten with emphatic nods of appreciation, with the exception of two or three pieces which one of them saved. He explained, by digging a hole in the ground and pretending to cover up one piece, that these were to be kept for seed, so that in the future they might have plenty of so delicious a fruit.

Of their religious life or the lack of it almost nothing could be learned from the bands we met along the Tambopata. At Maldonado, however, the newly established military post of Peru on the Madre de Dios, were two or three Chunchos from another river, who had become residents of the camp and had learned some Spanish. The commandant of the post and I spent some time trying to find out whether these savages have any idea of religion. The commandant, a good Catholic, attempted to explain to them some idea of God. They listened apparently in vague wonder, and when asked if their people had no such belief replied in the negative. The idea of a future life after death, so far as we could learn, was not familiar to them. At the present time there are several thousands of these savages living in scattered groups of twenty or more along the rivers flowing into the Madre de Dios. Many of them are just coming into intimate contact with the white race. A condition little better than slavery awaits them.

Is it a white man's country

For the present the chief interest in this great, undeveloped region lies in the fact that it is rich in rubber and a few other natural products. But what of its future? Is it "a white man's country?" Parts of it undoubtedly offer favorable conditions for white laborers, so far as climate is concerned. From the crest of the eastern Andes down to the level plains, every climate, from the frigid to the torrid, is passed in succession. This zone, however, is narrow and badly cut up into deep valleys with precipitous sides. Agriculture has its difficulties. It is stated that a farmer arrived one day at the Santo Domingo mine in very bad condition. Asked what had happened to him, he replied that the night before his farm had fallen on him. Landslides in this region are certainly frequent. Probably enough water power is going to waste on these slopes to do the work of the world. Within a short distance large streams fall in a continuous mass of foam 10,000 feet or more. Nor does it seem to me probable that the lower plains will be found especially unsuited to the white race. At present in these endless forests insects swarm in countless millions and malaria doubtless is prevalent; but, with the forests cleared away and with the comforts of civilization, the conditions would be much improved. The altitude is some 2,000 feet above sea level and the heat by no means extreme. During our journey on the rivers the highest temperature recorded was 960 F., and a temperature above 900 was extremely rare. One hesitates even in imagination to picture what manifold industries may be found among these foothills in coming centuries, and what millions of prosperous dwellers may be clustered on the plains at their feet.

Arequipa, the Chief City of Southern Peru |

Peruvian Station of Harvard College Observatory, near Arequipa |

Lake and Glacier in the Aricoma Pass of the Eastern Andes Altitude of the pass, 16,500 feet |

Mule Trail of the Inca Mining Company, Eastern Slope of the Andes |

Natives Living on the Tambopata River, a Tributary of the Amazon |

|

The Peruvian Military Camp near the River Madre de Dios |

* The author of this article was sent to the west coast of South America in 1889 to determine the best site for the Southern station of the Harvard College Observatory. He examined the west coast from the Equator to the southern coast of South America and upon his report Arequipa. Peru, was selected. Professor Bailey had charge of the work there for eight years, and has established a meteorological station on the summit of El Misti, at an elevation of 19,000 feet, where observations have since been carried on. It is by far the highest scientific station in the world.