The Filigreed Self

from The Creators by Daniel Boorstin

Proust went far to make the remembered self a resource for re-creating

the world. The refluent self became his “inner book of unknown

symbols.” But the self had other outreaching possibilities,

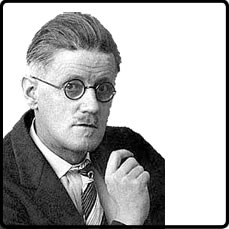

which James Joyce (1882-1941) explored with surprising consequences.

For Joyce, encompassed time was no mere private garden of involuntary

memory but a microcosm of all human history. This he chronicled

in no heroic figure on a grand stage but in “the dailiest day

possible,” not in a history-making capital but in a provincial

metropolis on the periphery. He folded time in by making his Work,

like Proust’s, the story of its own making and of the making

of himself. But he would also prove that Homer had never died.

Proust went far to make the remembered self a resource for re-creating

the world. The refluent self became his “inner book of unknown

symbols.” But the self had other outreaching possibilities,

which James Joyce (1882-1941) explored with surprising consequences.

For Joyce, encompassed time was no mere private garden of involuntary

memory but a microcosm of all human history. This he chronicled

in no heroic figure on a grand stage but in “the dailiest day

possible,” not in a history-making capital but in a provincial

metropolis on the periphery. He folded time in by making his Work,

like Proust’s, the story of its own making and of the making

of himself. But he would also prove that Homer had never died.

Joyce and Proust, to be coupled forever as pioneer explorers of the self, were near-contemporaries. Proust was only ten years older than Joyce, and they appealed to the same select audience. They did meet once, at a Paris supper party for Stravinsky and Diaghilev in May 1921. Proust, on a rare excursion from 102 Boulevard Haussmann, arrived late in a fur coat and was seated beside Joyce. The best account of this legendary meeting came from the American poet William Carlos Williams, who was there. “I’ve headaches every day,” complained Joyce. “My eyes are terrible.” To which Proust replied, “My poor stomach. What am I going to do? It’s killing me. In fact, I must leave at once.” As they left each expressed regret at not having read the work of the other. But Proust tried to enliven the conversation by asking Joyce if he liked truffles. To which Joyce replied, “Yes, I do.”

Joyce’s failing eyesight and the twenty-five eye operations that left him blind for periods had a self-confining effect like Proust’s asthma. Proust’s divided Franco-Jewish self had its counterpart in the self-exile of Joyce, whose life was a web of paradox. Never living in Ireland after his twenty-second year, Joyce remained passionately Irish. He explained to his publisher that his purpose in The Dubliners was “to write a chapter of the moral history of my country and I chose Dublin for the scene because that city seemed to me the centre of paralysis.” The city became his Mediterranean. From his birth he was entangled with the issue of Irish independence. His father, John, a passionate follower of the firebrand Charles Stewart Parnell (1846-1891), had made a living as one of Parnell’s election agents, then enjoyed his reward as a well-paid collector of taxes for Dublin, where Joyce was born in 1882.

Joyce’s first known writing was a poem at the age of nine attacking Parnell’s opponents. And his family’s fortunes fell with those of Parnell, in melodramatic decline when he was accused of terrorist murders in Phoenix Park (which Parnell’s men had not committed) and when Parnell was named correspondent in the divorce suit of a fellow Home Rule politician. John Joyce’s heavy drinking, neglect of his office, and habit of dipping into money from the taxpayers’ till were enough reason for his dismissal from his remunerative post. The family naturally charged up their misfortunes to the enemies of Irish Home Rule. In 1891 John Joyce’s family of ten children who survived infancy tumbled from prosperity to poverty. “For the second half of his long life,” James’s brother Stanislaus observed, “my father belonged to the class of the deserving poor, that is to say, to the class of people who richly deserve to be poor.” The insecurity of the rest of James’s young life left unforgettable memories of household furniture in and out of pawn, and moving about to stay one jump ahead of the bill collector.

Somehow James Joyce still had the benefit of the best Irish schools. At six he briefly attended an elite Jesuit boarding school until his family could no longer pay the fees. For two years after 1891 he stayed home under his mother’s tutelage, then in 1893 both brothers were admitted tuition-free to a Jesuit grammar school in Dublin. Then on to another Jesuit institution, University College, Dublin, where Joyce pursued languages and made his first literary sallies. Admiring the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906), at the age of eighteen he published (1900) a review of When We Dead Awaken (1899), where he contrasted “literature” that dealt with the temporary and the unique with “drama” that posed the laws of human nature. “The great human comedy in which each has share, gives limitless scope to the true artist, today as yesterday and as in years gone.” Lohengrin “is not an Antwerp legend but a world drama. Ghosts, the action of which passes in a common parlour, is of universal import.” To read Ibsen in the original, he studied Dano-Norwegian.

A message from Ibsen himself thanking him for his “benevolent” review made him ecstatic. In a letter congratulating Ibsen on his seventy-third birthday in 1901, Joyce confessed:

But we always keep the dearest things to ourselves. I did not tell them what bound me closest to you. I did not say how what I could discern dimly of your life was my pride to see, how your battles inspired me—not the obvious material battles but those that were fought and won behind your forehead—how your wilful resolution to wrest the secret from life gave me heart, and how in your absolute indifference to public canons of art, friends and shibboleths you walked in the light of your inward heroism.

On receiving his B.A. degree with second class honors in Latin from University College, Dublin, he went to Paris, where he toyed with the idea of studying medicine. Lacking both the academic qualifications and the tuition fees, he quickly returned to literature, supported by small sums from his mother. Coming back to his dying mother in Dublin in 1904, he sold to a farmers’ magazine (for one pound each) three of the stories that would later go into The Dubliners. On June 16, 1904 (destined to be known in literary history as Bloomsday) he fell in love with Nora Barnacle, whom he had met only four days before. Though Joyce refused to go through a marriage ceremony, they left together for the Continent in October. He would never again live in Ireland. First he tried teaching in the Berlitz School in Pola, near Venice, before he and Nora moved to Trieste, where their two children were born. They were joined by his brother Stanislaus. There Joyce taught English to businessmen. Then on to a brief distasteful stint in a bank in Rome. He visited Ireland briefly in 1909, to try to publish The Dubliners, and to start a chain of Irish movie theaters, and again for the last time in 1912.

When Italy declared war in 1915, Joyce moved from Trieste to Zurich. There he remained for the duration, piecing out a living by teaching English, selling short pieces, and enjoying patronage—from the Royal Literary Fund (seventy-five pounds), from Edith Rockefeller McCormick, and from the bountiful Harriet Weaver (eventually some twenty-three thousand pounds). In 1920 Ezra Pound induced him to move to Paris, where he remained until his death in 1941. He and Nora finally went to London in 1931 to be married to satisfy his daughter. Though he made a career of writing, he never really made a good living from it, only surviving on meager fees from short pieces supplemented by patrons.

Joyce, most modern of novelists, encompassed time in autobiography, creating new ways to make the self universal. Despite his migratory life of self-exile, his writing remained rooted in Ireland. His first published work was a volume of verse, Chamber Music (1907), which already revealed his witty mastery of the beauty in words. And his writing had an unfolding logic, astonishing from so vagrant an imagination. His collection of stories, The Dubliners (1914), offered the background for A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), which was his autobiography, and Exiles (1918), an Ibsenesque play of emigrants returning to Dublin, which dramatized Joyce’s own marriage problems. His masterpiece, Ulysses (1922), was a personal epic, and finally came Finnegans Wake (1939), intended to be an epic of all humankind. Except for short experimental pieces and brief volumes of poetry, this was his whole lifework. He showed wonderful progress from the most objective and external ever inward and toward the self, finally penetrating to a new language of consciousness. Yet as his subject matter became more self-bound and his purpose and meaning ever broader, his style grew more arcane, his language more cryptic. His way of conquering time revealed the limits of the self, the need to reach out through community. But he was finally tempted to make language into a self-regarding ornament.

He brought together the two modern literary forms, the novel and biography, as none had done before. And incidentally, in the progress of his writing he provided a summary history of modern literature—from narrative in the human comedy of The Dubliners, to biography-autobiography-confession in The Portrait of the Artist, to ruthless exploration of the self in Ulysses. Unsatisfied by the unique self and its experience, he found refuge in the ancient community of myth. But his self-preoccupation did not leave him alone. Finally in Finnegans Wake he made his very language a toy, an embellishment and labyrinth, of the self. As his works became more self-absorbed they became harder to understand and less accessible until finally they reached the outer limits of intelligibility.

The Dubliners, a collection of stories about the daily life of his city, was mostly written in Trieste in 1905. And it shows what Joyce meant when he called Dublin the center of Ireland’s paralysis. Without melodrama or suspense, they reveal the everyday frustrations and disappointments of a disgraced priest, of an unconsummated love, of a compromised girl, of the electioneers for Parnell and Home Rule. This was Joyce’s album of the “moral history” of his country, of the faiths of ordinary people. The final haunting story, “The Dead,” he added, after his brief unhappy interlude in Rome, to fill out his portrait of Dublin. “I have not reproduced its ingenuous insularity and its hospitality, the latter ‘virtue’ so far as I can see does not exist elsewhere in Europe.” He made the simple story of a Dublin Christmas party a parable of the rivalry between the living and the dead. His efforts to have The Dubliners published were a foretaste of his lifelong publishing tribulations. Publishers objected to his use of the word “”bloody,” his disrespectful reference to King Edward VII, and his naming of actual streets and people. First refused by a London publisher, it was taken on by Maunsel in Dublin, who printed a whole edition. But then Maunsel decided to play safe, broke their contract, and had all (except one copy) burned. Joyce had gone to Dublin in 1912 to hasten publication, but when Maunsel destroyed his books he resolved never to return to Ireland. And he never did. He had a Dutch printer set up a broadside that he wrote especially for this occasion to be circulated in Dublin:

… But I owe a duty to Ireland I hold her honour

in my hand,

This lovely land that always sent Her writers and artists to banishment

And in a spirit of Irish fun

Betrayed her own leaders, one by one…

O lovely land where the shamrock grows!

(Allow me, ladies, to blow my nose) . . .

“Why did you leave your father’s house?” Leopold Bloom would ask Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses. To which Stephen replied, “To seek misfortune.” “The Dead,” as his biographer Richard Ellmann notes, was Joyce’s first song of the exile that proved to be his proper element. On leaving Ireland with Nora in 1904, he had promised a great book within ten years. The year 1914 was indeed his annus mirabilis, on which his lifework converged—when The Dubliners was published, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was substantially finished, Exiles was written, and Ulysses was begun. All were products of his residence in Trieste.

With the outbreak of the war in 1914, instead of being interned by the Austrian government Joyce was allowed to go to Zurich, which became his headquarters for the next five years. A Portrait of the Artist which bore at its conclusion “Dublin 1904/Trieste, 1914” was Joyce’s first plunge into himself, an autobiography in the character of Stephen Dedalus of the first twenty years of his life. He recounted his infancy, his childhood, Clongowes School and the university with unprecedented fluency and candor.

The line between Stephen Dedalus’s consciousness and his external experience is dissolved. After this immersion Joyce could not withdraw. His friend Herbert Gorman, who knew him when he was writing Ulysses, saw A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man as “the coffin-lid for the emaciated corpse of the old genre of the English novel. It was a signpost pointing along that road which led to Ulysses and which still stretches wide and inviting albeit stony and difficult for other novelists who would be among the outriders of our intellectual progress.”

Just as Boswell opened the gates of biography by recounting the trivial idiosyncrasies of an unheroic figure, so Joyce first dramatized the fantastic resources in the consciousness of a boy. So he made a narrative art of the flow of consciousness. Its grandeur came not from significant external events nor potent antagonists, but from the inner mystery. Proust, too, had found the well of involuntary memory rich and deep in childhood. Joyce finds drama and suspense in the inner struggles of young Stephen Dedalus’s discomfitures on the playground, his bewilderment before arcane Jesuit propositions, his pain at unjust punishment for his broken eyeglasses, his malaise of disbelief and of insecure belief, haunted by the terrors of hell. And his unease at hearing the priest tell him that he might have been destined for the Church. Dedalus’s conversations cover death, love, art, salvation—all the topics that figure in Joyce’s later works. Foreshadowing Ulysses, the style varies and progresses, from the familiar opening, “Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road, and this moocow… met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo…” gradually toward the mature finale:

Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.

27 April. Old father, old artificer, stand me now

and ever in good stead.

Dublin 1904

Trieste 1914

In Dedalus’s encounters at school and the university we meet some of Joyce’s most elegant, most eloquent, and often-quoted aphorisms.

Now, at the name of the fabulous artificer, he seemed to hear the noise of dim waves and to see a winged form flying above the waves and slowly climbing the air…, a symbol of the artist forging anew and in his workshop out of the sluggish matter of the earth a new soaring impalpable imperishable being?

Ireland is the old sow that eats her farrow.

To live, to err, to fall, to triumph, to recreate life out of life!

The artist, like the God of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails.

And even in this straightforward narrative of a boy’s education, word and idea interpenetrate. Words become ideas, the self’s inward product of a blurred vision of the outer world. Not in re-creating the outer world but in making words their own world Joyce the creator imitated God.

Words. Was it their colours? . . . No, it was not their colours: it was the poise and balance of the period itself. Did he then love the rhythmic rise and fall of words better than their associations of legend and colour? Or was it that, being as weak of sight as he was shy of mind, he drew less pleasure from the reflection of the glowing sensible world through the prism of a language many-coloured and richly storied than from the contemplation of an inner world of individual emotions mirrored perfectly in a lucid supple periodic prose?

The continuity of thought in all Joyce’s writing is not surprising, for it is all autobiography. He would expand the application of his ideas from childhood and adolescent tribulations to personal epic, and on to his epic of world history. Stephen Dedalus, whose young consciousness is chronicled in A Portrait becomes a hero of Joyce’s next book. A Portrait ends on April 27, 1904, and Ulysses picks up the autobiography in a new mode on “Bloomsday,” Tuesday, June i6, 1904. During the short omitted interval, Stephen has been in Paris, until his dying mother brings him back to Dublin. And as Ulysses opens, Stephen is living in the Martello tower at Sandycove with his friend the medical student Buck Mulligan.

Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed. A yellow dressinggown, ungirdled, was sustained gently behind him by the mild morning air. He held the bowl aloft and intoned:

—Introibo ad altare Dei.

Halted, he peered down the dark winding stairs and called up coarsely:

—Come up, Kinch. Come up, you fearful jesuit.

Solemnly he came forward and mounted the round gunrest. He faced about and blessed gravely thrice the tower, the surrounding country and the awakening mountains. Then, catching sight of Stephen Dedalus, he bent towards him and made rapid crosses in the air, gurgling in his throat and shaking his head.

But why Ulysses? Joyce’s reading had opened to him the world of biblical and classical myth, of Irish legend and history. At school, when his English teacher asked him to write an essay on his “favorite hero,” he had chosen Ulysses. So the vagrant Ulysses must have lingered on when Joyce sought a frame for his work about 1914. By then his own experience of exile had given the most famous ancient exile a special intimacy. Back in 1906 he had thought of a work to be called Ulysses at Dublin (in place of Dubliners) recounting the ordinary day of an ordinary Mr. Hunter. And then, halfway through A Portrait he began to see how Ulysses might provide the frame of his next book. The only competition might have been Dante’s frame for his Divine Comedy, which had engrossed Joyce and left its mark on all his work.

“I am now writing a book,” Joyce explained to his friend Frank Budgen in 1918, “based on the wanderings of Ulysses. The Odyssey, that is to say, serves me as a ground plan. Only my time is recent time and all my hero’s wanderings take no more than eighteen hours.” When Budgen seemed puzzled, Joyce asked him if he knew eany complete all-round character presented by any writer.e Budgen ventured Goethe’s Faust or Shakespeare’s Hamlet. To which Joyce retorted that not these but Ulysses was his ecomplete man in literature.e It could not be Faust. eFar from being a complete man, he isn’t a man at all. Is he an old man or a young man? Where are his home and family? We don’t know. And he can’t be complete because he’s never alone.”

No-age Faust isn’t a man. But you mentioned Hamlet. Hamlet is a human being, but he is a son only. Ulysses is son to Laertes, but he is father to Telemachus, husband to Penelope, lover of Calypso, companion in arms of the Greek warriors around Troy and King of Ithaca. He was subjected to many trials, but with wisdom and courage came through them all. Don’t forget that he was a war dodger who tried to evade military service by simulating madness. He might never have taken up arms and gone to Troy, but the Greek recruiting sergeant was too clever for him and, while he was ploughing the sands, placed young Telemachus in front of his plough. But once at the war the conscientious objector became a Jusqu’auboutist [bitter-ender]. When the others wanted to abandon the siege he insisted on staying till Troy should fall.

Later, when Joyce said he had been working hard on the book all day, Budgen asked if Joyce had been “seeking the mot juste.” He already had the words, Joyce said, but was seeking “the perfect order of words in the sentence. I think I have it.”

I believe I told you that my book is a modern Odyssey. Every episode in it corresponds to an adventure of Ulysses. I am now writing the Lestrygonians episode, which corresponds to the adventure of Ulysses with the cannibals. My hero is going to lunch. But there is a Seduction motive in the Odyssey, the cannibal king’s daughter. Seduction appears in my book as women’s silk petticoats hanging in a shop window. The words through which I express the effect of it on my hungry hero are: "Perfume of embraces all him assailed. With hungered flesh obscurely, he mutely craved to adore." You can see for yourself in how many different ways they might be arranged.

In his Odyssey of the eighteen hours of Bloom’s and Dedalus’s day Joyce combined a scrupulous verisimilitude with extravagant symbolism. He pored over maps of Dublin and made sure that his book could be read in the same length of time in which the events occurred. In 1920, writing to the critic Carlo Linati, Joyce attached a Homeric title to each chapter, along with its own hour of the day, a dominant color, a technique, a science or art, an allegorical sense, an organ of the body, and symbols. After revising the scheme in 1921, he sent it to a few critics and to Stuart Gilbert to be included in his James Joyce’s Ulysses (1930). But when Sylvia Beach published Ulysses in Paris in 1922, Joyce had suppressed the Homeric tags, leaving his reader the challenging Joycean opportunity to explore for himself.

Joyce did generally follow the Homeric story of the wanderings of the heroic warrior. Homer’s first four books (the Telemacheia) tell of Odysseus’ son Telemachus, unhappy at home in Ithaca, then visiting the mainland for news of his father. The eight following Homeric books recount Odysseus’ wanderings and adventures in the twenty years after the fall of Troy that took him from Calypso’s island to the encounter of the naked hero with Nausicaa, and the legendary encounters with Polyphemus and Circe. Finally, Homer’s concluding twelve books (the Nostos, or Homecoming) tell how Odysseus returns home and recovers his kingdom.

Joyce adapts this Homeric scheme to his own purposes. His first three chapters (his Telemacheia) offer a prologue of the daily life of Stephen Dedalus. When the book opens at 8:oo A.M. on Tuesday, June i6, 1904, Stephen is at home in the Martello tower in Dublin with his roommate, the medical student Buck Mulligan, and their visiting Englishman Haines. We see Stephen teaching his class at the school and the headmaster Deasy (Nestor) asking him to help secure publication of his article on the foot-and-mouth disease. En route Stephen is tempted by girls on the beach at Sandymount (Proteus). Then in Book II the other Ulysses-hero, Leopold Bloom, appears, also at 8:oo A.M. on the same day, preparing breakfast for his wife, Molly.

—Milk for the pussens, he said.

—Mrkgnao! the cat cried.

They call them stupid. They understand what we say better than we understand them. She understands all she wants to. Vindictive too. Cruel. Her nature.

Curious mice never squeal. Seem to like it. Wonder what I look like to her. Height of a tower? No, she can jump me.

—Afraid of the chickens she is, he said mockingly. Afraid of the Chookchooks. I never saw such a stupid pussens as the pussens.

—Mrkgnao! the cat said loudly.

These episodes are not told in the order of Odysseus wanderings, but do include counterparts to Calypso, the Lotus Eaters, the Voyage to Hades, Aeolus King of the Winds, the Lestrygonians, Scylla and Charybdis, the Wandering Rocks, the Sirens, Cyclops, Nausicaa, the Oxen of the Sun, and Circe. Joyce’s final three chapters, the Homecoming (Nostos), offer counterparts of Homer’s Eumaeus, Ithaca, and Penelope, as they converge the day of Stephen and Leopold. Stephen accepts Leopold’s invitation to a cup of cocoa at his 7 Eccles Street home. Stephen walks off into the night, and we are left with Bloom, whose Molly ends the book with the famous stream of her consciousness.

Joyce himself explained to Linati that Ulysses, besides being an encyclopedic cycle of the human body, was an epic of two races, the Jews and the Irish—both historic victims on the periphery of European history. Joyce seized his opportunity, using pagan and Judeo-Christian lore to rescue them both to the center of the human stage. The headmaster Deasy put the question:

—Ireland, they say, has the honour of being the only country which never persecuted the jews. …And do you know why?. ...

—Why, sir? Stephen asked, beginning to smile.

—Because she never let them in...

Ulysses is the story of itself. Ingenious theological interpreters see Bloom as God the Father and Dedalus as God the Son, who must be united by the Holy Ghost in the miracle of artistic creation. And the accounts of Bloom’s bodily processes affirm the universal humanity of the story. While the chapters recounting Dedalus’s day have their correspondences in the Gospels (the Last Supper, Jesus’ conflict with the scribes and Pharisees, the Temptation of Jesus in the Desert), Bloom’s day has its Old Testament counterparts (from Genesis to Elijah).

Dublin, a modern city-state, was providentially suited for the Joycean Odyssey. “It was . . . a happy accident,” Stuart Gilbert notes, “…that the creator of Ulysses passed his youth in such a town as Dublin, a modern city-state, of almost Hellenic pattern, neither so small as to be merely parochial in outlook, nor so large as to lack coherency, and foster that feeling of inhuman isolation which cools the civic zeal of Londoner or New-Yorker.” Joyce’s confidant in Zurich in 1918, Frank Budgen, luckily for us described the process of writing Ulysses. “Joyce wrote the ‘Wandering Rocks’ with a map of Dublin before him on which were traced in red ink the paths of the Earl of Dudley and Father Conmee. He calculated to a minute the time necessary for his characters to cover a given distance of the city. …Not Bloom, not Stephen is here the principal personage, but Dublin itself… All towns are labyrinths…” While working on his chapter, Joyce bought a game called Labyrinth, which he played every evening for a time with his daughter, Lucia. From this game he cataloged the six main errors of judgment into which one might fall in seeking a way out of a maze. Just as the Odyssey would become a geographical authority on the Mediterranean world, so Ulysses would be a social geography of Dublin, with no falsifying for effect, no “vain teratology” or study of monsters.

Joyce’s most celebrated literary innovation—the “stream of consciousness,” unspoken soliloquy, or silent monologue—was for him no flight of fancy but a device of realism, making art follow nature. Still, he disavowed credit for its invention. In 1920, as he was completing the last episodes of Ulysses, he explained to Stuart Gilbert that the monologue intérieur had been used as a continuous form of narration by a little-known French symbolist, Edouard Dujardin (1861-1949), in his novel Les Lauriers sont coupés (1887) some thirty years before. “The reader finds himself, from the very first line, posted within the mind of the protagonist, and it is the continuous unfolding of his thoughts which, replacing normal objective narration, depicts to us his acts and experiences.” Joyce’s own way of revealing, exploring, and recounting the secret sources of the self by the interior monologue was already inviting imitation even before the whole of Ulysses was published in book form, for parts were being published in the little magazine The Egoist. Joyce set the example in the stream of Molly Bloom’s consciousness, the last forty pages, which he explained to Budgen:

Penelope is the clou of the book. The first sentence contains 2500 words. There are eight sentences in the episode. It begins and ends with the female word ye, It turns like a huge earthball slowly surely and evenly round and round spinning Its four cardinal points being the female breasts, arse, womb and cunt, expressed by the words because, bottom, woman, yes. Though probably more obscene than any preceding fertilisable untrustworthy engaging shrewd limited prudent indifferent Weib. "Ich bin das Fleisch das stets bejaht."

… or shall I wear red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall an I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to as again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower an first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.

To make his book universal, Joyce drew heavily on anthologies, handbooks, compilations, and textbooks. Critics have marveled at the prodigious learning revealed, for example, in the “Oxen of the Sun” chapter, written in the different styles of the periods of English literature in chronological order. But their authenticity comes from the fact that they are mosaics of the authors parodied, drawn from their very words found in two textbooks Saintsbury’s History of English Prose Rhythm and Peacock’s English Prose from Mandeville to Ruskin. Joyce, never forgetting the self, found ways to make this progress of styles symbolize the growth of the human fetus in the womb.

Ulysses, like Joyce’s other works, was focused on the act of creation in the arts. Significantly he had finally titled the first part of his autobiography revised from his earlier Stephen Hero, “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” By naming his autobiographical hero Dedalus after the “fabulous artificer” of wax wings, he depicted “a hawklike man flying sunward above the sea, a prophecy of the end he had been born to serve and had bee following through the mists of childhood and boyhood, a symbol of the artist forging anew in his workshop out of the sluggish matter of the earth a new soaring impalpable imperishable being?” Like Proust, Joyce made his work the story of its own creation. By adding Bloom he chronicled the divided self in Ulysses, the commonplace alien part of the artist, the Jew always in exile.

In Ulysses Joyce re-created the mystery of art and the universe. “Here form is content, content is form,” as Samuel Beckett would say of Finnegans Wake. “His writing is not about something, it is something itself.” And a mystery, too—realist, naturalist, symbolist, parodist, comic, epic—of countless levels, embodied and enshrouded in the Word.

Still, the cryptic depth of Ulysses did not faze censors across the English, reading world when the book was published by Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company in Paris in 1922. The authorities struggled to protect the public from the frank interior monologues and from a few taboo words. Five hundred copies of the Egoist Press London edition were burned that year by the Post Office authorities in New York, and 499 of their third printing of 500 were seized by the English customs authorities in Folkstone. But the censor’s efforts eventually enlivened the Federal Law Reports with a concise and favorable review of Ulysses by Judge John M. Woolsey. He found it “not an easy book to read . . . brilliant and dull, intelligible and obscure by turns,” but not obscene.

Joyce has attempted—it seems to me, with astonishing success—to show how the screen of consciousness with its ever-shifting kaleidoscopic impressions carries, as it were on a plastic palimpsest, not only what is in the focus of each man’s observation of the actual things about him, but also in a penumbral zone residua of past impressions, some recent and some drawn up by association from the domain of the subconscious. He shows how each of these impressions affects the life and behavior of the character which he is describing.

Eleven years after Ulysses first appeared in English, in that same first week of December 1933, when Americans repealed their Prohibition of alcoholic beverages, Judge Woolsey determined that Americans should no longer be prohibited from reading Joyce’s “true picture of the lower middle class in a European city” and sharing Joyce’s effort “to devise a new literary method for the observation and description of mankind.” Although certain scenes were strong medicine for “some sensitive, though normal, persons to take . . . my considered opinion, after long reflection, is that whilst in many places the effect of ‘Ulysses’ on the reader undoubtedly is somewhat emetic, nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac.” And since there was no law against importing emetic literature, he ordered Ulysses to be admitted to the United States.

Where to go after Ulysses? There seemed no place to go, either in realistic depiction of daily life or in symbols to give art and grandeur to the trivia of the conscious self. “I will try to express myself,” Stephen Dedalus had declared, “in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using for my defence the only arms I allow myself to use—silence, exile, and cunning.” Joyce’s cunning in elaborating and embroidering Everyman’s self was limitless and undaunted. He had taken on the vocation of a writer but had added little to his outward experience in a world of turmoil. He spent the years of World War I under the umbrella of Swiss neutrality in Zurich writing Ulysses. Now at the war’s end he went to Paris at the invitation of his patron and mentor Ezra Pound. With his vision confined by near-blindness, he turned deeper inward. And not merely to the resources of involuntary memory. He re-created his language into a refuge, a sanctuary, and a whole New World of the self.

Ulysses, as Judge Woolsey had certified, was surely “not an easy book to read.” To one uncomprehending American reader, Joyce explained, “Only a few writers and teachers understand it. The value of the book is its new style.” On other occasions he was less patient with the obtuse audience. At the end of one evening in Paris soon after Ulysses had been published, his melancholy at the cool reception of his book had been deepened by strong drink. As the taxi delivered him home to his door he ran up the street shouting, “I made them take it!” But a full decade would pass before he could make Englishmen or Americans “take it.” In 1932 he was still trying to persuade T. S. Eliot to publish the book in London for Faber & Faber. While willing to publish episodes in his Criterion Miscellany, Eliot would not take on the whole book and Joyce refused to allow publication of either an abridged or an expurgated edition. “My book has a beginning, a middle, and an end,” he insisted. “Which would you like to cut off?”

Meanwhile he spent himself on what he only called his “Work in Progress,” which would occupy him for sixteen years from March 11, 1923, when he wrote the first two pages—“the first I have written since the final Yes of Ulysses. Having found a pen, with some difficulty I copied them out in a large handwriting on a double sheet of foolscap so I could read them.” Just as Ulysses was the sequel (in a new mode) to A Portrait, so Finnegans Wake would be a sequel (in another new mode) to Ulysses. As Ulysses had ended with Molly and Leopold eating the same seedcake (Eve and Adam eating the “seedfruit”), now Finnegans Wake would begin with the Fall of Man—symbolized in the fall of the hero of the music-hall ballad, the hod carrier Finnegan, from a ladder to his “death,” then his resurrection by the smell of whiskey at his wake. The new novel would incorporate and exploit many leftover ideas from the twelve kilos of notes that he had collected for Ulysses.

Compared with Finnegans Wake, Ulysses would be simple clarity itself. Here the admiring reader of Joyce meets his match, and is reluctantly driven to a heavy reliance on interpreters. Even the puzzled serious student comes to feel that he is trying to understand the ground plan of an elaborate filigreed castie in a treatise by its architect written in an only partly intelligible code. Is the plan itself all there is to the castle? We know much more about how the book was made than of what it was. Does Finnegans Wake describe anything, or is it itself the thing? The book reminds us of an existentialist parable. A man sees a “For Sale” sign outside a house and goes up to ask the price. To which the occupant replies, “Only the sign is for sale!” Does Finnegans Wake tell us about anything beyond itself?

It is one of those books, Anthony Burgess reminds us, “admired more often than read, when read rarely read through to the end, when read through to the end not often fully, or even partially understood.” Burgess has dared help us with A Shorter Finnegans Wake. Other intrepid critics, Joseph Campbell and Henry Morton Robinson, “Provoked by the sheer magnitude of the work . . . felt that if Joyce had spent eighteen years in its composition we might profitably spend a few deciphering it.” Why has so eloquent and lucid a writer as Joyce spent his energies teasing us with a book of colossal proportions, of 628 dense often-unparagraphed pages, with its puzzling plenitude of invented words, multiple puns, and onomatopoetic inventions? Is it inconceivable that this master of the comic may have launched the biggest literary hoax of history? But generations of readers still assume that it is they and not the author who is amiss.

Whatever else it is, the book is the ne plus ultra of the literature of the self. Perhaps at this dead end the book is something only the author (and he only partially) can understand.

What was it about? “It’s hard to say,” Joyce told a sculptor friend, August Suter, in 1923. “It is like a mountain that I tunnel into from every direction, but I don’t know what I will find.” He had already christened it “Finnegans Wake,” omitting the apostrophe because it was about both the death of Finnegan and the revival of all Finnegans (Finn-again).

In another time sense, too, it was a sequel to Ulysses. As Ulysses was a day book, he had already decided that Finnegan would be a night book, with its own special language. “I’m at the end of English” (Je suis au bout de l’anglais), he confessed. “I have to put the language to sleep.”

In writing of the night, I really could not, I felt I could not, use words in their ordinary connections. Used that way they do not express how things are in the night, in the different stages—conscious, then semi-conscious, then unconscious. I found that it could not be done with words in their ordinary relations and connections. When morning comes of course everything will be clear again. . . . I’ll give them back their English language. I’m not destroying it for good.

The theme of this night story was the whole history of the human race. “Art is the cry of despair,” Arnold Schoenberg observed in 1910, “of those who experience in themselves the fate of all mankind.” And a night story it should be, for Stephen Dedalus had explained in Ulysses that “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” Though Joyce’s history was veiled in myth and in his private language of sleep, Finnegans Wake was still a story designed to be everybody’s—of the fall and resurrection of mankind. The comical fall of Finnegan with which the book begins is only a prologue to the entry of the hero, a stuttering Anglican Dublin tavern-keeper, HCE—Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, or Here Comes Everybody, or Haveth Childers Everywhere. A candidate in a local election, HCE had once reputedly committed an exhibitionist act (Original Sin?) in Phoenix Park before two girls. This memory and rumor never cease to dog him, and he is also cursed by an incestuous passion for his daughter. After several bouts of gossip, of changing winds of public opinion, and trivial misadventures, HCE is arrested for disturbing the peace, which seems to express his own obsessive guilt.

Earwicker’s wife, Anna Livia Plurabelle (ALP), is the woman of many forms—Eve, the mother at the Wake, the River Liffey which changes from the nymphlike brook in the Wicklow Hills to the drab filthy scrubwoman river that drains the city of Dublin in its circular course into the Ocean, then up into mists to fall in mountain rains to refresh the brook again. And we hear Anna Livia’s complaints of those who soil her currents:

Yes, I know go on. Wash quit and don’t be dabbling. Tuck up your sleeves and loosen your talktapes. And don’t butt me—hike!—when you bend. Or whatever it was they threed to make out he thried to two in the Fiendish park. He’s an awful old reppe. Look at the shirt of him! Look at the dirt of it! He has all my water black on me. And it steeping and stuping since this time last wik. How many goes is it I wonder I washed it?

The reader ceases to be puzzled, and simply wonders at Joyce’s bardic music when he hears Joyce’s recorded voice reading the liquid words of Anna Livia Plurabelle.

Their twin sons were curiously modeled on two feeble-minded brothers whom Joyce had known in Dublin. eShem the Penmane (Jerry: the artist, man of thought, explorer of the forbidden) and “Shaun the Postman” (Kevin: the practical political man of action) reveal again the eternal conflict between the Bloom side and the Dedalus side of Everyman in all history. All this is in mythic tales of flesh-eating and stories like “The Ondt and the Gracehoper.” Their conflict is finally resolved in the reunion of their father, HCE (from whom their two natures originated), with their all-embracing mother, ALP, in a diamond wedding anniversary.

But the story is not as easy to follow as the ordinariness of the intelligible characters would suggest. Joyce himself gives us a clue in the opening words of the book:

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodious vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

A way a lone a last a loved a long the

Vico’s scheme of history described each community rising from the “bestial” and passing through three stages: the Age of Religion and the Gods, the Age of Heroes celebrated in poetry and ruled by custom, and the Age of the Peoples expressed in prose and ruled by laws. The last stage results in anarchy, and the return to relive the cycle (corso).

It is surprising that Joyce should have turned from poetry to philosophy, from Homer to Vico, for the frame of his final work. But in an age when the arts were turning inward, exploring and re-creating the self, it is not surprising that he chose Vico, sometimes called the first modern historian. While others had seen history as the chronicle of men and events or the unfolding of a divine providence, for Vico history was a saga of the human consciousness, of man’s different ways of seeing himself. Against Descartes’s view of history as the unfolding of reason, which was the same in all ages, and of man’s encounter with nature, Vico focused instead on the self. Man, he said, was capable of understanding only what he could create. Since man had created culture, he could understand it, could observe the universal stages in his consciousness, reflected in the institutions of his making. Vico’s New Science was a science of the stages and cycles of human consciousness. Joyce used Vico’s scheme to fold the whole history of the race into Finnegans Wake. For Vico, like Joyce, gave primacy to language and myth and justified Joyce’s re-creating the language as the sanctuary of the self.

So, in his own way, Joyce accomplished what Gertrude Stein, also in Paris, hoped for—to be “alone with English,” but with his own re-created English. Joyce’s Finnegans Wake was a letter to himself that neither the writer nor the recipient fully understood—“that letter selfpenned to one’s other, that neverperfect everplanned.” It is not surprising, either, that it would entice and frustrate generations of interpreters.

Finnegans Wake was his “essay in permanence,” still another Joycean way of conquering Time. “A huge time-capsule,” Campbell and Robinson, his pioneer interpreters, explain. “The book is a kind of terminal moraine in which lie buried all the myths, programs, slogans, hopes, prayers, tools, educational theories, and theological bric-a-brac of the past millennium.” Yet this miscellany of the past revealed a universal pattern of repetitive recurrence, Joyce’s way of denying time.

Joyce’s ultimate accomplishment in symbolism was to make his final book almost as unintelligible as the whole mysterious universe. Finnegans Wake, Joyce himself confessed, was addressed to “that ideal reader suffering from the ideal insomnia.” Knowledgeable interpreters call it “one of the white elephants of literature”—“notoriously the most obscure book ever written by a major writer; at least, by one who was believed not to be out of his mind.” Yet the riddle of Finnegans Wake reflected no obscurity or confusion in the author. It re-created the language with unfathomed possibilities. And when Murray Gell-Mann in 1964 needed a name for the newly discovered ultimate particle of matter and found that there were three of them in the proton and the neutron, he recalled from Finnegans Wake the exclamation, “Three quarks for Muster Mark!” So Joyce’s ultimately unintelligible language provided the name for the ultimately intelligible particle of matter.

Asked why he had written the book as he had, Joyce mischievously answered, not in apology but as a boast, “To keep the critics busy for three hundred years.” Perhaps Joyce shared Einstein’s wonder that “the eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility.” Joyce’s final “extravagant excursion into forbidden territory” made the language of the self an invitation to rediscover and delight in the mystery.