Presentations Are Performances

or

Why There’s No Business Without Show Business

Every renowned figure in history, famous or infamous, beloved or reviled, understood the power of drama. Churchill’s speeches — uttered word for word by a phlegmatic predecessor — could not have inspired and rallied an entire free world. Sir Winston was a consummate, and not altogether unconscious, showman.

[…]

Children learn by imitation. Their words, manners, and attitudes are, like their drawings, imperfect copies of those they have seen somewhere else. They also learn over a span of time. So do we all. Locked deep in our minds is the pattern by which we even conceive the idea of time. It is memory. We remember a past, live in a present (which we know will slide into the past), and by extension and faith, assume a future. To be human is to have this sense of time. We cannot imagine learning everything known about some field in one illuminating instant, and would be suspicious of someone who told us he had. We know that understanding takes time. Probably no one really knows why, but there are clues. Giovanni Battista Vico (1668-1744), an Italian philosopher, distills a lifetime of wisdom in a short statement on human temperament: “Men at first feel without observing; then they observe with a troubled and agitated spirit; finally they reflect with a clear mind.” Notice the implication of time passing by the use of “at first,” “then,” and “finally.” If Vico is right, as I think him to be, then by linking his insight to the concept of learning by imitation we have a key both to the nature of drama and to methods for the presentation of ideas.

In drama the actors imitate for us and allow us to see what happens to them all — from outside the action — as the story unfolds. But how does the story unfold? In all first-class work, it unfolds according to Vico! Analysis of great plays shows them to have three main parts: statement of a problem; development of inner implications; solution of the problem. These are sometimes put in this way: crisis, conflict, resolution. Often, our familiar division into three acts faithfully follows this plan. In homely terms, there must be a beginning, a middle, and an end.

It is curious how art forms, games and sports, humor and scientific method, all possess a similar structure. Musicians have their sonata form, which they say consists of statement, development, and recapitulation. Chess players describe opening, the middle game, and end game. Jokes involve description of a situation, placing two views of it in conflict, and a punch line. Scientific method uses Hypothesis, Inference, and Verification. It appears, then, that a trinity is important in many places besides theology. In fact, one could make a good case that the promulgation of the early Christian ideas enjoyed a tremendous enhancement by casting them in this form and structure, which is most congenial to human minds. (Additional force was realized by coupling its structure to one of the best methods for maintaining interest: The Trinity has been taught as a Mystery, i.e., its nature can never be fully known by human intelligence. By such means an idea can tantalize great minds forever.)

What is the lesson here for us with more limited ends in mind? Simply this. Present your idea in this structure and sequence: statement of the problem, development of its relevant aspects, and resolution of the problem and its development. Use this structure and you send your idea rolling down the well-worn grooves of the human mind. Ignore it and you send it into rocky, unknown canyons from which it may never return.

The rest of this book will relate in one way or another to this tripod of Statement, Development, and Resolution. Unlike the theological Trinity, it contains no mystery. But putting it under every idea, for maximum stable support, still allows full play for human ingenuity, from cookbook recipe to the heights of inspiration. At this point, reflect on the presentations you have experienced, both failures and successes. Did not every success satisfy this structure? Did the failures? If the failures met this test, did their ruin then lie in the performance skills employed?

By now I hope we have shown that presentation of an idea is an art — built on principles, yes, but still an art. A work of art has two parts: Composition and Performance, each complementary to and affecting the other. The previous concepts of structure dominate the Composition aspect of the presentation. In this part no audience is present, and design, selection, rejection, and sequence are decided. This is the homework, meditation or conference phase, where the form is hammered out by sketching in, erasing, destroying, reconstructing, testing, and regrouping. When one is engaged in this stage, he is companion to Brahms, alone with his piano, or Picasso, brush in hand, spattered with paints. As Ben Shahn says in The Shape of Content, no critic, however hostile, would ever defend the mutilation or destruction of a canvas presented for exhibition. The community of critics would fire a fearsome volley of moralistic essays condemning anyone who did so as a barbarian unfit for civilized society, even if some of them agreed with the taste that prompted the violence. And yet, Shahn points out, a painter continuously destroys the picture as he builds it. Shahn says that two sides of the character, constantly wrestling for supremacy, are engaged: the builder and the critic. The builder tries and suggests, the critic shakes or nods his head at every attempt or result. Few of us can carry on this kind of internal battle with the intensity of great artists, but the same process is set going once one sets out to present an idea. Our critic sits on a stool with three legs labeled statement, development, and resolution. However, this internal critical process is often so exhausting that it gives rise to this piece of wisdom: “Great works of art are never finished, they are abandoned.” Critics have more endurance than builders, inside ones most of all.

Assuming, then, that out of this struggle finally comes a composition of the presentation for our idea, what next? At this point we have only an architect’s plan, a messy score, a copy of the play, a sketch of what is to be done. Now comes performance. Here we set down a principle: Performance can never add to the intrinsic merit of a composition; the most it can do is to harm it as little as possible. However, bad performance can take a first-class composition and turn it into rubbish. The shrewd reader may now sense a false note in that he has often read reviews where it is said that the performer triumphed over his material. These are usually in connection with plays or music. True; but the composer or playwright is not very happy with such a review, for he has not succeeded in presenting his idea. The critic has commented on the skills of the actor or performer, probably out of kindness to him. He is applying a set of standards, not to the idea presented, but to the skill used to do it. This kind of review is the epitaph of failure. It is similar to remarks heard when a lovable man has tried to present an idea too demanding for his performance skills: “I didn’t understand what he was getting at, but he sure is a warm human being.” Those satisfied with that accolade should not read on.

Performance skill available will, or should, exercise a powerful constraint on composition. In presenting an idea, the level available is often your own, your superior’s, your subordinate’s, or at least someone else’s who will be doing the job, presumably someone known to you. You do not enjoy the freedom of the musical composer who writes for the ages, or the playwright who expects only experienced stars to speak his immortal lines. Beethoven once replied to a complaint that his violin concerto was unplayable, “To hell with your damned fiddle!” (in German, of course). Presentation of an idea must keep an uneasy but vital three-way balance between content, composition, and performance. (We will discuss the subsidiary balance between style and content in a later chapter.) Consider these illustrations.

A beginning piano pupil, playing a piece geared to his level, produces murmurs of approval, even from a virtuoso present. But what happens if his beaming parents then set before him something for the concert hall? Parents keep beaming, perhaps even hold hands, but the child perspires and guests remember other appointments. When a fine actor makes records of classic children’s stories, he gives them new meaning for adults, for he brings out more of their intrinsic merit than we had recognized before. But if he lavishes talent on the trivial, boredom soars, and we question his judgment or, at least, his agent’s.

To sum up, the performance can be no better than the material, but good material can be ruined by bad performance. Old vaudevillians knew this in their bones, but to judge from many current presentations, this awareness declined at about the same pace as vaudeville itself.

There may be a social mechanism at work. In the past, when most knew less, emphasis went to craft and performance. For example, Greek sophists concentrated almost entirely on method. Today we emphasize ingestion and absorption of knowledge, and neglect disciplined expression. We have tried to tap the creative potential of the multitude by encouraging the formation of opinion, and giving everyone a chance to express it. But we seem to have set in motion, like the Volstead Act, a furious concoction of home-brew. Few knew how to bottle it properly for use by more than their circle of friends. Ideas are home-made, but even good ones need good bottling to stand rough use. Opportunity knocks.

Statement of the Problem

One of the clichés of our time holds that it is far easier to come up with solutions than it is to “define the problem.” Unkind cynics satirize eager enthusiasts for new tools and techniques as people frantic to find a problem that fits their solution. Some of the most pitiful presentations are made by such enthusiasts. They delight in explaining the mystery of a technique, usually at great length, as though they were magicians showing how a trick is done. But they neglect to excite interest by performing the trick itself first. If the attention of the audience is not engaged by showing how the tool or method will benefit them before the loving explanation of how it was developed and operates, a gloomy cloud begins to fill the room, and written on it for all to see is the blunt statement of failure: “So what?” When these two violent words bob around on the listener’s stream of consciousness, you’d better harness them as additional force for your presentation, or they will wreck the rest of your idea.

Skillful presentors know just how long to let these words float before resolving the tensions they produce in the minds of an audience. They answer the rude, but silent, question at just the right point. This advanced technique will be treated later in Chapter 4. I will only say here that it is related to mystery and suspense, and requires both deliberate design in the Composition stage, and steady nerves and sense of timing in the Performance stage. But when “So what?” is generated spontaneously by careless design or inept performance, your idea is on a suicide mission.

Rule 1: The only reason for the existence of a presentation of an idea is that it be an answer to a problem. This problem must be stated explicitly sometime early in the presentation.

If you think you can break this rule, you are better than the best essayists, novelists, and dramatists in history. So far, none of them has ever done so successfully. The statement of the problem is like a lighthouse. You may thrash around in a hurricane of thought, whip up storms of rhetoric or lie becalmed, but the rhythmic flash of the light allows the audience to keep their bearings. There are many ways to keep the problem flashing in the audience’s mind, and the choice is yours, but it must be made. Restatement of the problem periodically throughout the presentation offers a great field for the play of ingenuity, for the restatement (except in revival meetings) should always be different in form, but not in content. This is especially true in a lengthy or complex presentation. The use of visual aids makes this quite easy, but it is a scandal how seldom it is done. Perhaps just because it is so easy, it’s considered unnecessary. Like breathing air, we only notice the process when we feel in danger of asphyxiation. Taking things for granted is as hazardous in presentations as it is in personal relations.

Rule 2: Never overestimate the audience’s information or underestimate their intelligence. Repetition of the sense of the problem, but in different words, satisfies this rule. Repetition is related to rhythm in every form of art. Its appeal springs from that most primitive aspect of physiology — our pulse.

Let’s assume that some constellation of forces has propelled you to the launching pad, and you must make a presentation. It doesn’t matter what the forces are: divine revelation, an order from the boss, an attack on your previous position, a routine agenda, an invitation to address a group, just plain irritation at the way things are, or a genuinely creative insight, which must be expressed. In order to satisfy the requirements of drama and interest, you must find a way to state the problem plainly. Everything else in the presentation will be built on it. Variations of the plain statement will come easily to you later. Some arise in the Development stage; or, since it’s more fun, when others volunteer ideas to help with the decoration. But the simple statement of the problem that caused you to stand before the audience is truly hard work. If it is done badly, the structure of the entire presentation will be shaky; if it is not done at all, you are well advised to catch a diplomatic virus or break a leg. Silence is still the best substitute for brains, though it is not yet an absolute replacement.

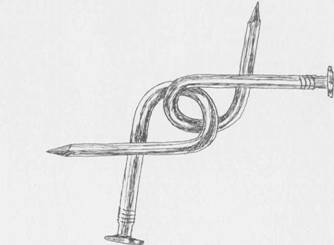

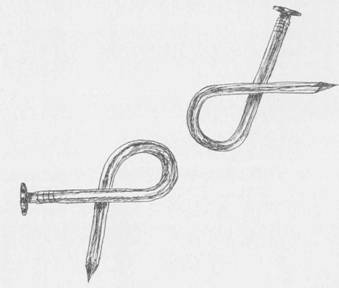

Just what do we mean by a problem? Think of some problems you know of right now: personal, family, career, business, community, national, or global. What do they all have in common? One thing, at least. All problems consist of a mismatch between two things: what actually exists and what we want to exist (in our desires and imagination). Since we also perceive events taking place in a stream of time, a problem’s solution must be in the future. Some time, short or infinite, separates the present set of unsatisfactory circumstances from those we want to replace them with. These two aspects, mismatch between two conceptions, and their separation in time, furnish the clue to why other human minds can become interested when a problem is stated explicitly, and why they founder if they have to guess at what the problem is. A good way to visualize these qualities of a problem comes from a simple puzzle. Consider two nails, bent so that they can be linked or unlinked only by placing them in relation to each other in a special way.

|

The puzzle, or “problem,” is to separate the two bent nails. |

Note that two images are mismatched, the nails linked and the nails separated, and that we “see” the desired state because someone told us: “This is the problem — separate them,” causing an image of them separated in the future to cross our mind.

Puzzles intrigue us, often to the point of obsession, because the two states are very clear, and because we know there is a solution. If you can state your problem with the clarity of a puzzle, and strongly suggest that a solution is possible, you can seize and focus that magnified interest that puzzles have extracted from great minds and small since prehistory. Archeologists have found puzzles in every human culture. In fact, one could make a good case for defining man as a problem-solving animal. It would seem to be a little more general and appropriate (if one takes a close look at some of our contemporaries) than adjectives like “rational,” “social,” or “tool-making.”

Consider, though, what happens if the puzzle is not presented as a puzzle, but only as an artifact or object. It may be beautiful, or interesting for other reasons, but unless the person receiving it guesses that it is a puzzle, interest will quickly fade. Even if he guesses that it is one, should it be complex, he may not guess what the intended objective is. These circumstances of ignorance or confusion cause the subsequent behavior of the recipient to differ from what the puzzle designer desired. From our viewpoint, there is a failure in the presentation of an idea. Recollect presentations you have experienced where the problem was never made explicit. Did they not resemble putting forth the puzzle as a mere object, and not as something to be changed?

Select your favorite simple puzzle and use it as a handy mental gauge of problem-statement. Secretly recall it when a problem must be defined. You will be surprised at how few preliminary definitions meet the simple tests of: “What exists?” and: “What do I want to exist?” Used discreetly with others, these two razors have fashioned the reputations of “those who get to the heart of a problem.”

If you do not already belong in this group and wish to join, here is the initiation fee: Use them.

Looking at the task of stating the problem in this way, we can glimpse its help in the two subsequent stages of Development and Resolution. At every step we refer to the two pictures of what is and what should be. We can also see how conflict, the dramatists’s form of development, flows out of good problem-statement. In those elegant solutions, which we call creative, two viewpoints, both correct in themselves, throw light on each other and illuminate our vision with new possibilities. Thus, dual pairs of opposites have been used in all works of powerful persuasion: love and hate; life and death; strength and weakness; fear and courage; disease and health; rise and fall; war and peace; right and wrong. Relating a problem to themes like these guarantees that your audience will grasp its association to their own lives, for we have all been there before. These pairs are really explosive code words for the two conditions mismatched in a problem. What we call our lives are probably tracks of careening from one problem to another through time, some solved and most postponed.

While mismatch is at the heart of every problem, clearness in describing the desired thing, state, or situation is vital. Without it, the vision dies. If your audience does not grasp the one situation in the future that is the objective of your idea, you will often see them exhibit symptoms that psychologists find in neurotics. Fidgeting, compulsion to flee, anger, hostility, daydreaming, indecisiveness, phony note-taking, and microscopic fingernail inspection are forms of self-defense when people are forced to consider ambiguous objectives. There are good reasons for the similarity of symptoms, for neurosis is that state where two conflicting desires remain equally strong. Energy, yearning to do one thing or the other, refuses to be kept bottled up by delay. It finds outlets in various ways, but unrelated to both of the warring objectives. Different persons use different outlets, but usually develop habitual responses. Everyone has seen these, but perhaps not observed them. Here are some I’ve experienced, and I submit them only as triggers for your memories.

One high corporate official always listened with great interest shown on his face, legs always crossed. As long as the presentation held his interest, his legs were steady. As the presentation became confused, his foot would begin moving, increasing in amplitude. The unlucky proponent either resolved the ambiguity, at which the foot would dampen its oscillation, drifting down to zero, or the official, unable to cope with his by now gyrating shoe, would stand up, thank the miserable character, and flee. Throughout, he never let his face betray his true feelings, and this probably subjected him to more frustration than those with less control could put up with. I knew him for many years and believe that he never realized how he had diverted the effects of emotion from normal facial reactions to his feet. If anyone had told him, the sharp-eyed would have lost a very useful telegraph, at least until the energy involved had found a new conducting path.

Another eminent man always carefully rolled a sheet of paper and peered through it as a boy does in playing sailor with a cardboard tube. Years of practice made the act one of polished elegance and often charmed visitors who did not understand its meaning. One engineer would move to a different chair. A brilliant attorney, known for his self-control and courtly manner, invariably sent a message (to those knowledgeable) that he had sustained a setback, or was about to object, by picking up his pencil, holding it in midair eight inches above his table for a few seconds, and then laying it down with scrupulous care and precision.

I have indulged in this little digression, not as a lesson in detective procedure, but to illustrate that a failure in problem statement can be sensed even at the last minute if one knows what to look for. The failure may be caused in the performance, even though the composition had it well thought out. If you are prone to this kind of failure in problem-statement, there are several techniques to overcome it. (In those situations where visual aids are acceptable or customary, straightforward statement or representation is relatively easy. We will discuss the special techniques of visual aids in Chapter 6.)

Here are some approaches useful for getting the problem stated explicitly. These tag words are for convenience and brevity in later discussion, and the labels should not be thought of in their narrow dictionary sense. The examples, I trust, will make clear their over-all meaning. Remember, the two criteria they must serve are to show a mismatch between the present and the future, and a difference in time span between the two images:

Historical Narrative, Crisis, Disappointment, Opportunity, Crossroads, Challenge, Blowing the Whistle, Adventure, Response to an Order, Revolution, Evolution, The Great Dream, Confession.

HISTORICAL NARRATIVE

This is the method of the storyteller. By recounting a tale of what happened in the past, and bringing history up to the present, our inborn sense of continuity in stories — learned in the nursery — creates a momentum which projects the story into the future. To children, “They lived happily ever after” is a fine ending, but it is not too useful for idea presentation. As the narrative sweeps on, adults know that the “story” in the future can turn out in many different ways. Your idea must select one of these ways and show why the state it leads to is a good one for the audience.

Example: “Our town began as a trading post, grew to be an important manufacturing center, survived many disasters, and produced fine people. We must bequeath to our descendants and heirs better than we received. ‘ therefore, I believe that we all want our town to . . .” (grow, become richer, be cultured, be cleaner, be beautiful, have better schools, or whatever other objective you want for the town).

By this projection, you have stated the problem, i.e., how to arrive at the state you desire from where you are now. The narrative approach offers rich possibilities for the development stage by drawing parallels to the past, remembrance of shared nostalgic values, adulation of previous outstanding contributors whose standards of achievement stimulate competitive instinct, and suggesting sad decline and an unhappy ending of the story unless your idea is accepted.

The generality of this example can be seen by substituting for “town,” nation, family, club, business, church, school, or any other institution with some history. The historical narrative subtly suggests that the successful course was the result of personal decisions by men in the past, and that personal decisions today by members of your audience can be equally effective.

(This personal element differentiates it from the approach I call Evolution. The assumption that the story has been one of success to be proud of differentiates it from Revolution.)

CRISIS

In Chinese, the ideographic character for crisis combines the two symbols for “danger” and “opportunity.” The crisis method of stating a problem makes use of this ancient insight by sketching out the danger facing the audience, and showing that an opportunity exists to extricate the audience from the danger — if they accept your idea. This method should not lay blame for the crisis on the audience, as the Old Testament prophets did. (That method is covered under “Blowing the Whistle.”) It is best done by showing the audience a quick succession of indisputable facts to establish that a danger exists. Only after that is done are they in the frame of mind to examine the array of facts to find a way out. Your idea should come as a well-thought-out response to the facts. If your proposal is appealing, the anxiety caused by the gloomy recitation will be transformed into support. The greater the danger described, the more potential energy is available for support.

This method carries a hazard in that neither selection of the facts nor their cumulative effect must create so much anxiety that the audience is unable to think because of panic. That is the point where inciting to riot begins. Excessive anxiety will also lead to contradiction, or charges that omission of contrary elements has caused the crisis to be exaggerated. In this situation the audience will seek immediate relief by embracing these contradictory views, and your idea will seem unnecessary. You may even hear nervous laughter — a physiological form of relief from the intolerable tension you have unwisely built. Experienced debunkers wait for such excesses to launch their attacks; they are generous with rope and always give more than enough.

Example: “We have just received the results of our operations for last month. They’re not good — in fact, they’re bad. Our products are not even holding their own. A large firm has entered our market with a brand new division, staffed with their best men. They are selling substitutes for our line of high-profit items at 10 percent below ours. The union is demanding a 5 percent increase in wages. Our stock is being sold short very heavily. Bank loans are due in three months, and we have large tax payments to make in five. Our product inventory is rising, even though we have cut back production substantially. We cannot ignore this crisis any longer. We must formulate a program for every area of our company so that everyone will know what we intend to do about it, and what we expect them to do. At stake is the very survival of this enterprise. Here is how I propose we cope with this most difficult period in our history.”

Then comes your idea. If pessimistic, retrenchment and drastic cost-cutting may appeal to you. If optimistic, here is where those development projects get their chance, or increased sales effort and imaginative, radical marketing methods are embraced.

The crisis method, if skillfully used, announces that every part of the institution will be called on for its ideas and contribution. Some of the great ideas in every institution’s history have had to lie in wait for a crisis in order to get a hearing. These are high points in human affairs. However, if the crisis is exaggerated, disbelief rushes in. Backfire can also come from too much repetition. Good people will hunt for other allegiances. Leaders, surprised and delighted at the teamwork and enthusiastic drive produced by a crisis presentation, can become addicted to it quite easily. Followers never like it more than once or twice in a lifetime. Before using this method, be sure to find out the last time it was used. Someone in your audience is bound to remember, and will often point up embarrassing parallels at an unfortunate moment in your presentation.

DISAPPOINTMENT

This method of problem-statement is required when some plan in the past has miscarried. If the plan was well known and generally approved by the audience, they are extremely sensitive to any possible blame and are anxious about their faulty judgment in agreeing to the plan in the first place. Wisdom counsels that you reassure them that neither of these two fears are appropriate before you present your idea as a response to the disappointment. Recapitulation of the assumptions they had to make when authorizing the original plan allows you to show how they did the only thing possible with the facts then available, and that no one could possibly have known of facts that only came to light after things were underway. Once the audience senses that you are not going to blame anybody there, they will be emotionally receptive to an objective statement of the mismatch between what they hoped would come about and what actually did — i.e., the source of the problem that caused the presentation to take place.

If the objective of the past plan is still good, it is well to state why, for then the failure was one of methods used, and your idea goes to them. However, if the original objective must be abandoned as either infeasible or no longer valid, this must be made explicit, or there will be confusion as to what you propose. If there were dissenters at the time of the original acceptance of the aborted plan, they will be basking in a feeling of “I told you so,” and unless you draw their teeth early, their words will have inordinate weight when your own idea is discussed. It is usually best to recognize their previous positions, even by name, and subtly put them on notice that, instead of reiterating their previous views, they should apply their proven insight to the problems now at hand.

If your idea for coping with the general disappointment is well received, you will find an enthusiastic response far beyond what you have a right to expect. Its source is the gratitude and relief that: “We really did the best we could, and maybe everything will be all right after all.”

Example: “It is my painful duty to report to you the results of changes we made last semester in the content of our course in English Literature II. You will remember that we completely reorganized both the approach and required reading because of complaints from students and our newer teachers. They felt that the existing course was too heavily weighted with obsolete works and lengthy classics whose meaning and relation to modern life were obscure. They felt this prevented a real appreciation of literature from developing. We appointed a committee of several in this room to reexamine the course, study complaints, investigate what others were doing, and then recommend a program for approval. This dedicated committee worked hard and long and produced a well-thought-out, if revolutionary, plan. You will recall the excitement and enthusiasm most of us experienced when it was presented last year. True, some of you, like George Draper there, warned us of some of the pitfalls ahead, and while we all respected his characteristically wise counsel, I’m afraid we outvoted him without realizing how correct his predictions were.

“From the point of view of satisfying the students and teachers we had great success, and English Literature II stimulated more interest and appreciation of good writing than ever before. But we underestimated one important hazard — the State Regents Examination. This year we received the lowest evaluation ever in the scores our students achieved, and we may even have harmed their chances for college selection. This is a grave responsibility. We know our action was good education, but we must also recognize that our results are judged by these allegedly impartial tests, which we do not compose or control. They still reward adherence to the old course. I’m afraid we were a little ahead of our time. I hate to see us lose the good we have produced with the new, but we must not create undue burdens for our students. I will propose one way we might cope with this dilemma, and this time, George, we will really listen to your advice and counsel.”

The Disappointment type of problem-statement should always face the problem squarely, but look forward in its emphasis to hope, rather than backward to blame. Its danger lies in attributing blame to those not present to defend their position. True fairness to them is the best course, for they may get a chance for rebuttal later, and you might have to eat your words. This counsels that the blame be placed on unexpected events, outworn traditions, or other impersonal forces.

OPPORTUNITY

The opportunity problem-statement springs from the existence of possibility heretofore not available. A mismatch essential for a problem to exist lies in a new image of the future — one never imagined or presented before — compared with what presently exists. External events, inventions, new knowledge, discoveries, and techniques alter our view of what we could previously plan for before the opportunity arose. The audience can appreciate what the new opportunity means only if it is related to the past and present frustrations, limitations, and barriers to progress that the opportunity promises to remove. These hindrances must be presented and accepted as true before the proposal can have any appeal.

Once these are out on the table, the nature of the opportunity must be quickly sketched in, demonstrating how it overcomes these previous constraints. Then one must describe what life will be like if the opportunity is seized, and some of the consequences if it is not. However, the possibility that “others will take it if we don’t” always carries a threat that must be deftly used, or the audience may get a whiff of blackmail. Such an impression can poison subsequent digestion of your idea. (This point is often much better left for cross examination.) It is advisable to delay the discussion of what is needed to seize the opportunity until you are certain that the image of the future described is an appealing one for the audience. They will have been worrying about paying the piper right from the start.

Opportunities are always open-ended. Since no one really knows where they will lead, it is wise to indicate only roughly the more distant possibilities that the opportunity at hand opens up. If you get too specific, you may find the audience homing in on these secondary images, where you are bound to be short on evidence and long on shaky speculation. Specificity and certainty about these far-off possibilities marks you as too visionary, or a fanatic. The audience will discount your present proposal and avoid future ones. Practical men know there is many a slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip. They are often willing to settle if they can just be sure to get the cup off the table and let things go from there; but they justifiably resent the babying or condescending hand that insists on guiding the cup right on up to their teeth. Claims for panaceas are outlawed by the Food and Drug people. They should also be banned from presentations as strictly as they are from medicine cabinets, for they are purchased only by the ignorant.

Example: “I have never come to a meeting with more enthusiasm, and I am glad that you are all here for what may be a historic moment in the history of our industry. You know how hard we have worked to lower the costs and improve the quality of the steel we make, and how meager and disappointing our progress has been.

“Every time we got some new chemical discovery, it cost too much; and every time we tried to get more steel from existing plant, the quality went sour. On top of this we have had to raise our prices just to stay in business, and the public’s impression of us has gone down every time prices went up. We have really been frustrated in our efforts to do a better job, and while we have achieved a plateau of development and built the industrial base of the country, our competitors in aluminum, glass, and especially plastics, have cream-skimmed markets once entirely ours. We have also experienced unfair competition from those abroad who have the very latest equipment financed by foreign aid programs.

“If ever an industry needed and deserved a breakthrough, ours is that industry; and, gentlemen, it is my happy duty to report one. Many people have been working on processes using high pressure oxygen in various ways and have had little success. Keeping alert for any possibility, we heard rumors recently that a small firm in England, extending a process developed in Austria, had licked the problems. We immediately sent off several of our best scientists and engineers for on-the-spot investigation. I received their final reports late yesterday, and the results are fantastic. We must quickly make up our minds about this opportunity — the greatest since the Bessemer converter — because the plans we agreed to last month will be affected in many ways, depending on how you react.

“One of the most surprising aspects is that a new plant can be justified economically at one-tenth the capacity and size we experience today! It also handles a larger range of mixes, and cheaply delivers quality tolerances better than we can hold today. The ultimate implications for steelmaking throughout the world can’t even be imagined yet, and I won’t waste your valuable time by speculating on them. But this process seems to be the answer we’ve been hoping for to solve today’s problems — and yesterday’s — and we have plenty to do just to insure that we don’t miss the boat. We have many ways we can react, and after the technical people here describe the process and its benefits, I will present my view of the choices we have and their consequences for all of us here.”

Notice that the opportunity method constantly suggests that action will be required by the audience, even in recounting the present. Interest can be sustained in the Development stage by means discussed later, but the onwardness of movement should never stop. The audience must become convinced that the opportunity is theirs, not yours. If an opportunity type presentation stops after merely a description of the event that produced it, the audience is left up in the air, and your idea joins the trash pile of lost opportunities.

CROSSROADS

Problems of the “crossroads” type result from a past success or achievement. One can picture them as that place on a journey where, if one wants to continue the trip, a choice must be made between two or more available routes. The old road behind has run out, and those ahead fork to right and left. Your presentation is not a plea for taking a specific road, but instead, attempts to establish that you are now at a point where a choice must be made.

Graduation from high school is a homely example. It is an instantaneous state and marks a success point. Here it is obvious that a choice for the future must be made as a result of the present success. It is not at all obvious in other problems of this type. Making an audience aware of the necessity for choice is more difficult than one would think, for situations involving a larger group of persons and circumstances are never as clear-cut as the graduation of an individual. There will always be some in the audience who believe that the momentum of the past achievement can best be continued by not touching anything and letting well enough alone. Your job is to show that this possibility does not exist. Crossroads presentations are sometimes mixed with an opportunity presentation, but in my experience this is a mistake. You are confusing the audience by statement of two problems simultaneously, and it will plague the entire development of both. A far better technique is to make two presentations with some time between, if possible. If not, then the crossroads problem must come first, and let the break be signaled by having two different people address themselves to the two different problems. The crossroads problem demands a change, the opportunity problem allows a change. This difference may appear subtle, but it is quite profound from the viewpoint of the audience.

Example: “After the acceptance last week of our report, plans, and specifications for the water pollution project, we must face the decision on what to do with the fine team we assembled for the job. All fifty of the people assigned were hand-picked experts in their fields and in the last year have learned to work together far better than we could have hoped. In fact, we did not expect to have to hold this meeting for another three months on our original schedule. We did expect to be asked to make many more adjustments and modifications to our plans, but the Commission’s complete acceptance, while most gratifying, has caught us by surprise. You all know how difficult it was to recruit this organization, what a fine leader we developed in John Hustle, and it seems a shame to disband it. But we do not have any more jobs like that in the offing, and we’ve got to face it. The contractors would undoubtedly like to hire some of the engineers, and we have existing projects which could benefit from additional personnel. But their disposition in many different ways is not the problem here. We must decide very soon what we intend to do, so that we can allay the anxieties I know are building up, and deploy the people in both their best interests and ours. We have developed a few possibilities, and Clark will present them this afternoon, but before we discuss them, it is important for us all to agree that this project team must be redirected. Does anyone have anything to add at this time, before I go into more detailed consideration?”

While this sounds quite simple, you will generally be surprised at the tendency to maintain the existence of a successful entity. In fact, most institutions have many enclaves formed of the remnants of once successful groups. This is the result of never presenting the problem as a crossroads problem to higher authority. There are always some loose ends to every activity, and they can be woven into marvelous, if fantastic, designs. Unraveling them has made more than one consultant’s reputation and fortune. Unrecognized crossroads problems, if left to breed, grow material for both comic and tragic plays.

CHALLENGE

A problem presented in the challenge format announces the call for a contest. The mismatch here is between the images of what exists and what someone else dares you to accomplish in the future. The idea of challenge rests on the existence of obvious obstacles to be overcome, much like the labors of Hercules.

Obstacles may be an assault or race against an impersonal force, like climbing a mountain or beating a speed record; achieving a level of quality or beauty never before experienced; or meeting a test for survival in the face of a hostile force.

The challenge triggers primitive emotions of rivalry, self-preservation, and the fear of being thought cowardly by those who know you have been “called out.” The method has been used by every great captain and every good platoon leader since the Bronze Age. A game or contest gets its emotional impact from identification with the contestants by the spectators who share the challenge vicariously. The limits of the challenge form are that it be neither too easy nor too difficult. With too little challenge there is no image of real triumph offered as the goal; but a truly impossible challenge results in apathy, a refusal even to imagine a triumph. Both reactions prevent recognition of a problem. When used well, few methods of problem-statement -an equal it as groundwork for colorful, emotional development. ‘Put up or shut up!” is its shortest form.

Example: “For years we have all complained that we do not have a good local theater. Well, now we have a chance to get one, but it will take every bit of effort we can muster. As you know, the State Arts Festival is scheduled in two years, and the Nord Foundation — out of the blue — has told us that they will match, dollar-for-dollar, any funds we can raise ourselves. We can’t just sit on our hands and hope. We’ve got to acquire a site and have an approved architect’s plan in their hands in nine months. Also, if we do not have the theater ready two months before the Festival, the deal’s off. This is a tough challenge, but we are not likely to get another chance like it for a long time.

“We may fail and be the laughing stock of the state, but we also might succeed and show other donors what kind of people we are. The Foundation has put it to us fair and square, and now it’s entirely up to us. Before you answer, let me take you through some of the important factors in this problem.”

The challenge type problem is similar to an opportunity problem, but differs in that the emphasis is placed more on overcoming obstacles than exploiting an unexpected event. It also differs from most crisis problems as it is offensive rather than defensive in character, though of course a crisis is the pathological form of challenge.

BLOWING THE WHISTLE

A policeman discovering an unlawful act and then summoning help and attention exemplifies this type of problem-statement. Mismatch exists between behavior observed and behavior demanded. The image of what is demanded is embedded in a set of principles, laws, customs, orders, or conscience. Greek tragedies and plays of Shaw are the supreme examples of what can be done with this method, and the everyday dramas of magistrate’s court use it in the less artistic way. The mismatch always implies that action is needed to bring the observed behavior in line with the code that has been violated. If this is not possible, punishment of some kind is to be dispensed, and steps taken to rectify the damage done.

It is essential that parts of the code be made explicit, either by quoting them directly or by reference to the pronouncements of authorities accepted by your audience. Facts concerning the actual behavior should be contrasted with the relevant citations. It is usually better to recite the facts first and the code provisions next. Though effective statement can interlace the parts of both, in ping-pong fashion, this sometimes leads to confusion in unskillful hands. You should also indicate quite early whether your idea goes either to providing punishment or to rectifying damage done. Mixture of these alternative objectives allows clever rebuttal and defense to show the audience that you are distracted and unclear, and that should they accept your idea, they will slide with you into an unwholesome state of confusion.

By selecting one or the other, cumulative, repetitive insistence on the need for future adherence to the violated code can build to a crescendo of feeling, like the bass drum in a funeral march. But refusal to make the choice will result in your audience not knowing what you want them to do. They hear simultaneous notes from piccolos and cymbals, sometimes interesting but never cumulative. When they do not know your objective, your chances of achieving it decrease with every word. If you must have both punishment and program, then split the story into two self-contained presentations. It is a rare or trivial institution in which the same people must take identical action for punishment as they must for programs of rectification or corrective action. Courts do not carry on the constructive work of society; neither do administrators sentence criminals. They are in two different games and play by different rules, yet both adhere to the same code of desired behavior. What makes them different is the different action expected of them when given the same problem.

Example: “In the past year the number of complaints about the fees charged by our physician members has increased alarmingly. We have tripled those of the previous year, and the press is getting interested. There also seems to be a pattern developing in the various specialties which some may infer as due to collusive practice. We have investigated thoroughly more than half of these complaints, and they seem justified. This disturbing development is completely contrary to the intent of the principles we agreed on last year, but the qualifying exceptions we put in to redress the unfavorable position of physicians in low-income areas seem to have been exploited by those for whom they were never intended. We need not discuss any action which our society should take against individuals. That’s a matter for our special review board. But we must face up to what we need to do if we want to regain the trust and respect of the public at large. Not all are at fault, of course, but since we will all be judged by the actions of a considerable minority, we must develop programs and procedures to safeguard patients and physicians alike. These must be so explicit in detail, without clever escape clauses, that we can take a position before a hostile press conference. I will present my ideas for your consideration after we discuss the details of several cases and their violations of the code to illustrate the problem.”

This method is not too effective if its entire thrust is based on altruism and moral force alone. You must always keep in mind the reason for the existence of the codes themselves: the preservation of the authority and position of the members of the institution to which it applies. If you can show the audience that the violations put them in peril, they quickly see the problem as important and requiring solution. A respectful hearing is then automatically guaranteed, whether the institution is a church, university, legislature, or industry.

ADVENTURE

A risky and uncertain image of the future is compared with the seeming safety of the present to produce a problem of the adventure type. Its appeal is based on lure of the unknown and a chance to test a person’s or institution’s mettle by engagement with hazardous, unpredictable forces. Enough information about the hazards is necessary both to establish the possibility of success and to stimulate the latent desire for excitement. Hints must be given about the gaps in knowledge or experience that the successful adventure will fill. The most difficult task in using the adventure type of approach is to establish why these gaps are important to eradicate, and what benefits will attend those who undertake, or underwrite, the search. Unless you secure this kind of momentum for your idea, it will screech to a halt when someone in the audience applies the peremptory brake: “Is this trip necessary?” You can visualize Thomas Jefferson persuading Congress to authorize funds for Lewis and Clark’s proposed expedition as an elementary form of this statement type. If your taste runs to the classics, substitute Jason’s proposal for the Golden Fleece recovery to the champions of Thessaly. This is the most exhilarating form of problem, but remember that the acceptance of your idea will depend almost entirely on the confidence you command with the audience. They must balance their fear of the unknown by faith in your leadership. If the scale comes down on the wrong side, no sale.

Example: “We have all heard complaints that the basic unit in our organization needs revision. We have listened to a dozen proposals for different rearrangements to improve customer service, optimize capital use, motivate employees, get a better technical job, and allow lower-level supervisors to take more responsibility. These ideas have all been well intentioned and ingenious. Yet their proponents have never been able to satisfy our fears that we will lose more than we will gain because of possible disrupted relationships, confusion, jurisdictional misunderstandings, employee resistance, loss of specialized knowledge, and customer irritation. Of course we will never have the kind of information and experience we want until we try, and we will be caught in this illogical circle of indecision forever.

“I propose that we set out to determine just what we need to know about these fuzzy areas so that we can settle, for at least the near-term future, what we should do. The trial I want will be a hazardous project and will require you to take chances that we are not accustomed to. We may fail or lose our nerve, but even then we will know much that we don’t know now. We need not put the whole outfit on the line, but we must be willing to involve three entire districts, about two thousand people, in the experiment for two years.

“I am convinced this is the only way, and while I prefer less risky forms of tinkering with people’s lives, that is just not possible. We can’t test these ideas in a laboratory. We must see if they can stand the heat of combat in the real world. I feel they can, but can’t be sure. Since the potential rewards of success are so great, I am willing to bet my reputation on them, and I know that many others feel the same way. The rest of our presentation is designed for one purpose: to convince you that we should have this chance. While we may conduct the operations, you must share in our triumph or defeat. We will not and cannot launch this without your support.”

If you choose this method of problem-statement, abandon the ancient hedging maneuver of deploying a well-balanced list of “pros and cons.” That is too often a subtle device for passing the buck to superiors and directly opposes the sense of adventure: a willingness to endure the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune for a higher goal. Adventure sounds a call to arms, not summations to the jury.

RESPONSE TO AN ORDER

The problem here is rooted in a comparison between the state of affairs someone else wants (a superior or other authority) and current conditions. Orders are usually resorted to after persuasion fails, and are most often unwelcome to their recipients. Stark statement is preferable to pussyfooting. The greatest difficulty is to get the audience away from a mood of “It’s unfair, we don’t deserve this, can’t we fight?” and other forms of childish behavior. If you are really serious about resolving the problem, it is not advisable to identify with the sense of being wronged. The objective of this problem statement is to get all of the audience’s irritation and anger diverted to constructive suggestion. Any castigation of the order-giver will plague you later, when you must defend the basis of your ideas for resolving the problem. More important, dissatisfied elements who disagree with your proposals may even use your opening remarks to quietly inform the order-giver that your solution is as bad as your stated opinion of his order. This can become embarrassing when you need his approval later for your program of response.

After stating the problem and indicating that it will not disappear in a cloud of wishful thinking, a factual description of the forces and considerations that caused the order to be given helps dissipate the emotional voltage, and channel it into mature reflection. If you can get the members of the audience to imagine that they would give the same kind of order were they in the order-giver’s place, you are halfway home. Another positive step is to show that the order-giver has confidence in the audience’s ability to deliver the goods, and that if successful solutions are forthcoming, his opinion of the group will rise.

If you cannot state these things as heard directly by you, the same effect, somewhat diminished, flows from a speculative explanation of “what must have been in his mind to give us this order.” The final polish to an unpopular problem-statement comes by developing some variation of the belief that: “It’s an ill wind that blows nobody some good.” If a few in the audience come to believe that an opportunity lurks somewhere in the order, their mental energies can be brought to a hot focus. However, constructive response cannot occur if the audience “fights the problem” or refuses to come to grips. These attitudes must be demolished before development begins, or your idea will neither be heard nor understood.

Example: “Yesterday we received the final order from the city which forces us to put all of our pole lines inside the city limits underground. We have exhausted every appeal, but all we could do was to get the period to comply extended from the original one year to two. We can do nothing more. All of you have been working on the alternate approaches, but they must now be discarded. I’m sorry, as I know you must be, but we don’t have a day to waste talking about it anymore.

“If we were in the City Council’s place, I suppose we would have done the same thing sometime, but not as quickly. They don’t seem to understand the difficulty of the job. One even told me, ‘You people are real professionals — you’ll work it out. We know you can do it.’ We have talked about this amongst ourselves for some time, but now we have to do it. I know a few of you, particularly Jack Goodfellow, have tried to sell us on this for years. We will now see whether your arguments about lower repair costs and fewer interruptions in service are any good. You will have every chance to prove it. The public relations people also see this as not too bad, since it ought to cut out a lot of the complaints we’ve been getting recently. We must face the fact that a majority of citizens just don’t like poles and wires cluttering up their view. So let’s get on with it. We must have a complete program drawn up within the month if we are to obey the order.”

This approach has another merit for the development stage. Since the order must be carried out, arguments for countermoves and delay can always be referred back to the necessity to comply. Once an audience decides that the order needs to be met, they are jealous of any time wasted on unnecessary discussion. Ready-made plans, in line with an order and loaded with detail, are impregnable to possibly better ideas, which are still only in the sketch or conceptual stage. This is where contingency planning pays off. Superior planning groups are those with a shelf full of ideas waiting for customers. Their effectiveness is best seen in problems of the order type.

REVOLUTION

Revolution-type problems find their mismatch between an unfavorable image of the future, which will occur if the present state is left undisturbed, and a better state, which is possible only if the historical and traditional inertia is arrested and cast down. Things must be turned over (revolved) by drastic intervention, or they will only get worse. Revolutionists for big issues see themselves as benefiting unborn generations, almost as engineers of future history. Their best appeal is to the latent rebel and maverick element in each of us, which is our counterbalance to boredom. Fear of the consequences is their greatest obstacle. Mismatch between the images must be so great that the will to “solve the problem” overcomes the fear of the consequences of failure. Weak problem-statement will not allow development of a strong program. The audience will keep hoping to have their cake and eat it if you don’t show that the future demands scrapping most of the past — and much good along with it.

Revolution is akin to adventure, but with the hazards mostly known and predictable. Development uses these hazards as factors energizing the sense of self-preservation. Without them there is little need for the audience to submit to your leadership and gamble their destiny on the clarity of your particular vision. It appeals most to those with nothing to lose; least to those with much. Election speeches of the best type — by the “outs” — are polite forms of the revolutionary problem.

Example: “Our church loses vigorous members every month and gains only those tired of progress in their former congregations. Every day we act as though the great changes going on about us are unworthy of our concern. We keep looking backward, to a nostalgic day that really never was, hoping that all of our difficulties will disappear by magic. If we continue like this, we are headed for the ash heap, and our absence will be mourned by none except the hard-core reactionaries who have refused to see how sick we really are. We need a new look, a new mission, and a new management. Our present Council will keep reelecting themselves, holding things as they are, and treating us like a bunch of children. And yet under present rules they are the only ones who can make the changes required. We must reject them and establish a new order without them if we want this church to survive and to train our children properly. It will not be easy. We can expect the central authority to be prejudiced in their own favor. They are powerful men who can harass you and your families just for attending a meeting like this. They may try to expel us from membership. There may be bad publicity. But this tyranny must be ended if we want to be true to the ideals that built this congregation and made it, until recently, a force for good. The Council has betrayed our future by its petty and stubborn refusals to make even the slightest reforms required. It is up to us, the concerned and committed, to act on our own. Here is my idea.”

Revolutions take nerve and are successfully prosecuted only by the ruthless. No halfway measures will work, and your opposition expects none. Never put a problem in this form unless you mean to live with the consequences of success as well as failure. A revolutionary idea is sometimes confused with a nihilistic idea, where mere destruction itself is the objective. Revolution is a means to an end: the vision of what life will be like after success. It is constructive in intent. Emphasis should always be on that. The uproar in-between is merely the vehicle to get there. Correction of injustice is its noblest aspect; simple spite, its meanest. Choose well.

EVOLUTION

An evolution type of problem arises when an institution or person, well adapted to its previous environment, is faced with a change in that environment that calls for further adaptation to remain viable. It has to “be out of touch,” or “out of date,” and dissatisfied with that condition. Mismatch lies between the present condition and the image of congruence with society desired in the future.

Emphasis should be placed on past success, and the adaptations successfully made to achieve that success. Then the change in environment should be sketched in ways that bring out the maladjustments calling for action. It is essential to show the positive results of future adaptation. You must also establish that the environmental change is not temporary or, at least, is not going to reverse itself to the previously happy state when all was right with your world. Intelligent resignation to overpowering forces is its mood, not belligerent obstruction.

Example: “Our efforts for conservation of the great wilderness areas have been the model for groups all over the nation. We have, to the credit of our previous leaders, a continuous record of successful battles against those who wanted to despoil our natural heritage. It was saved and developed by men of vision, who sensed the tendencies of their times, and who mobilized mass opinion to their cause. We can be proud of the large preserves now forever safe from the commercial axe and plow. Generations after us will benefit.

“However, our very success can endanger this great accomplishment, for social forces beyond our control require some alteration in our present policies. The state’s population has doubled since we stabilized the wilderness acreage. All good recreational areas will have been developed to capacity in a few years, and the increasing population and urbanization will create pressures on the preserves. We can delay and fight scores of small legal actions, hoping to keep things as they are. But we will lose in the end, for one adverse ruling by the Supreme Court will destroy our position.

“We have always contended that our activity was for all the people against the exploiters, but in these cases, we will look as though we are against the people. We will appear to be out of touch with social problems and are bound to lose unless we adapt to the inevitable. We can anticipate and plan intelligently now, while we have time. We need to balance the interest between wilderness and recreational use, and shape viable programs. Otherwise we will be told what to do. We lack a grand design for orderly evolution. I propose one now.”

Everyone feels safer with evolution than with revolution, and a calm demeanor can reassure the diehards no end. The tone to strive for is that of a duchess dedicating a new steel mill on one of her ancestral estates: progress with elegance.

THE GREAT DREAM

The only method of presenting a Utopia, paradise, or hell-on earth as an image of the future in contrast to the present is to rely heavily on fantasy. Fantasy, used seriously, can often be presented without being ridiculous by recounting a vision or a dream. Its structure is imaginative rearrangement of real things or facts in new ways. Dreams are unhampered by factors like time, gravity, or other restraints. Engineers like to say that dreams do not build bridges, but that no bridge is built without one. A dream-type setting is one that makes a tremendous leap from the present, beyond the imaginative capacity of most. The objective is to let others share its vision. Almost all religious problems are of this sort, Western or Oriental. If an audience’s imagination can be extended to grasp the vision, then they see the problem and are willing to work on it. If they don’t see it, you are put down as a visionary, and they leave the presentation undisturbed. The mood of a happy dream is hope; of an unhappy one, despair. You should think of yourself as leading the audience on a climb up a high hill for the first time. When they reach the top, show them the beautiful vista below. If you intend frightening them, substitute gaping chasms and boiling, sulphurous springs. Joseph in Egypt was a great practitioner of this method and was equally good on both sides on the street.

Example: “I have just returned from Bourneston, the once great center of our shipbuilding industry. It was a depressing visit. I saw the squalor and inactivity that have replaced the busy yards, prosperous streets, and happy children of my boyhood there. I came away with sad memories of broken windows, rusty cranes, dilapidated buildings, and yellowed paper blowing about in the offshore breeze. It is truly a ghost town.

“But as I climbed the hill in my melancholy mood, the sun was setting, and its light restored the scene below to its natural beauty. The whitecaps and rocks glistened, gulls circled, and the rhythm of the waves lifted my spirits. I had a vision of what might be, and all the way back my enthusiasm continued to mount. I became convinced that this poor victim of economic storms can rise again. The same coast, forests, inlets, and beaches that originally drew the industry can now draw others who want to enjoy, rather than to exploit, the advantages nature placed there. This forlorn place could become one of the great resort areas of this region. The time is ripe. Other resorts are overcrowded or honky-tonk, and fine boating harbors are rare indeed.

“If enough of you will entertain this dream for just a while today, I can give you some facts and ideas that might turn the vision into something of beauty’, but alive and real instead of a dream. It may not be practical and will not be easy, but let’s see what you think might be done. At best, you may be surprised; at worst, we will have done a little homage to a once lovely spot.”

With this method, there should be an alternation of hard facts with aspects of the dream, like a photo of a junkyard, followed by an artist’s colorful rendering of “what it’s going to be like.” Back to a photo, on to another drawing, and finally to costs, schedules, and the other paraphernalia of real projects. One must also show that the nucleus of the idea can spread and gather momentum. Use statements of influential movers and shakers who feel kindly — even if passively — toward the idea, and allude to similar successes elsewhere. The objective is always to strengthen a belief in possibility; but it must be approached indirectly by building on desirability.

CONFESSION

The mismatch here lies between what the audience believes exists and what really does. It is a tricky form of problem statement, since all sorts of emotions are at work both in the audience and in the presentor. Use of this form calls for you to walk a high, narrow fence; one slip, and you’re down. If your confession threatens to involve the personal reputations of members of your audience, they will usually greet the disclosure with silence at the outset. You should not be misled; they are feverishly thinking of ways to extricate themselves. Worry about the real problem, and your reputation is secondary.

If delivery is nervous and disconnected, you don’t have a chance. The audience will see that you are in no shape to present an idea for the solution of the problem you’ve dumped in their laps and certainly are not the man to lead the way out. More than any other form of problem-statement, confession demands absolute concentration on the outcome you want. No matter how hot the recriminations or how violent the reactions, your personal resolve is the best lightning rod for the natural forces you have unleashed. They must be made to serve your idea, not to wreck it. As with all violent forces — like sea, fire, or wind — their control is difficult; but if harnessed to a specific purpose, they can amplify your own efforts.

Most people secretly and unconsciously enjoy hearing a problem of the confession sort, especially from one they considered above them in a hierarchical structure. In return for removing a previous invidious relationship, the audience will return sympathy, or at least pity, if their fears of being dragged down can be allayed. This is almost entirely emotional. Witness the public outcry at the disciplining of popular heroes whose clay feet are displayed when they make headlines from time to time.

Since Saint Augustine and Rousseau, the “Confession” has gripped the popular mind. This form ranges from the precincts of the highest literature to tiresome trash. Confession, while humble in expression, implies a manly act of honesty. It may be late, but it also bristles with silent pride. In confession’s noblest form, there is always an element of self-sacrifice for some great cause. When coupled with development based on mystery, the audience sits expectantly, waiting for the answer to their inarticulate: “Why did you do it?” They can always identify with failure; not often with success.

In order to quiet their fear, it is essential that you take full responsibility, even if not deserved. After that, the audience will listen to the problem and your solution. Once their own personal anxiety is relieved, they will generally become constructive. If you can get the audience to imagine that each of them would have acted as you did, were they in your circumstances, you are on the downhill grade to home. This makes it necessary to describe these circumstances. Blame, if possible, unfortunate developments outside anyone’s control, which you faced and tried to overcome for the good of others, especially for those in the audience. If your confession is one of having exceeded your authority, and success was gained because you took the risk, you may experience the heady reaction of applause and cheers. Disraeli, buying Egypt’s portion of the Suez Canal, on his own hunch, is your example here. If failure develops, you at least get points for courage. Avoid the tone of guilt; embrace, instead, an air of responsibility and tragedy if things went awry. You must show the way out with all the passion you can muster. Without that, the presentation becomes only grist for the mills of gossips.

Example: “It is with a feeling of jubilation that we are gathered here to celebrate the success of our first School Fair. Many of you argued and pleaded for years that it would be a success; that it would bring the parents together; and that it would allow us to support some of the worthwhile activities desired by our teachers. But we were always deterred by fears of financial failure. Yet a few months ago we decided to go ahead.

“You will recall that I promised we would get the stands, lights, and carnival decorations from an anonymous donor. This was my own belief, but during the happy and hectic week before the Fair, I had a call from this gentleman — whom I still cannot name. He told me that financial reverses forced him to withdraw his promised support. I know that I should have told the committee, but as I saw all of you setting up displays, the children running errands, the husbands at work on a thousand projects, I simply could not do it. We had such a slim vote of confidence that I feared those who counseled us against the adventure would say, ‘I told you so,’ and stop the work we had so happily begun. I feared that if we did not go on, we would never get another chance. I believed so strongly we were right that I gambled with the good name of our association. I admit I had no right to do that, and submit no excuse except excessive emotional commitment.

“After hearing our treasurer’s report and experiencing a sense of fellowship here tonight unique in the history of our association, I am deeply sorry at what I must tell you. We still have an unpaid bill which will take almost one-third of the total proceeds we have just cheered. I must ask you to honor this bill even though I exceeded my powers and imperiled the whole enterprise. There is no one to blame but myself, and I submit my resignation because of the danger in which I placed this association. I did it on my own responsibility, even though I knew I could not make it good if my judgment were wrong. I would not have missed the Fair for the world, and I must tell you in all honesty that I would do exactly the same thing again.

“Thank you for everything, especially for making a dream come true. I will try to answer any questions you may have and accept any blame you care to ascribe.”

Notice that even in this saccharine scene, the problem of a mismatch between the treasurer’s report and reality is stated for the audience. The suggested image of restored respectability for the audience must follow quickly, or their anxiety level will get out of control. This form of problem-statement can mislead you even when successful, for the initial identification of the audience with your act fades away quickly. You may find them looking at you a trifle uneasily when you are next on an assignment that carries discretionary powers. It is advisable to leave the premises as soon as you can, so that frank discussion of your disclosure can dissipate any emotional residue. If you’ve done a good job of problem-statement, those who saw your viewpoint will do a far better job of defending it than you possibly can. If no friends rise to this duty, then you are even better off by not remaining.

This form is akin to the “Disappointment” style, but here the disappointment comes though in an instant, like a clap of thunder. There is no time given to prepare for its effect. If a choice can be made between “Confession” and “Disappointment,” choose the disappointment method for greater ease, and confession for greater drama. It is no accident that communist lawyers prefer a “confession style” trial to a “blowing the whistle” type. Such trials are designed as educational experiences and are put on for all other citizens who are watching or reading about them. “Confession” problems produce much more identification and emotional punch. They are consequently far more effective for such purposes of state than a tedious game of charge and denial.

Anyone can drum up his own list of pigeonholes to classify problems. It is a healthy exercise only if it impresses on him the nature of a mismatch between two images. There is something in each of us that is disturbed by a clash of conceptions or images. If we are geniuses, the resolution of the right kind of clash may win a Nobel Prize. If we are parents, we may try different approaches to bend a child’s behavior toward our favored image. If we are leaders, we will try to get others to share our vision and put their efforts to our cause. If we are neurotic, we may get to enjoy the clash for its own sake, unable to decide which is the better. All attitudes, except the neurotic, lead to action; they attempt to achieve the better state. Merely stating a problem implies that some action is latent or about to happen, or you wouldn’t state it. If you have none in mind, don’t even begin.

To return to our triad of Problem, Development, and Resolution, the art and science of development rests on selecting aspects of possible action. Rearranging and relating them in different ways (so that ever new aspects appear) show that derivative problems flow from the original problem. After subtle logical and emotional repetitions, lead on to the resolution of the original problem. Finally, stress the favored image set forth in the original statement and leave the unfavorable one behind. In the analogy of an ocean voyage, the problem is to recognize that you are in Port A and want to go to Port B. The various difficulties and events on the trip furnish the development, and the anchoring in Port B is the resolution. This analogy makes it clear that everything that happens during the voyage is always referred to the objective of Port B, and grows out of the departure from Port A.

Presentations that do not keep their eyes, brains, and hearts on the anchorage at Port B can degenerate into random cruises. The passengers (your audience) who thought they had bought a ticket for some other place, even if unspecified, are usually exasperated if you return them to Port A. While this seems obvious, many presentations end in disaster because their proponents never knew where they wanted to go. These people are often perplexed and hurt at an audience’s reaction. “After all,” they think, “I know we came back to where we started, but it was really an interesting trip, wasn’t it?” Just as cruises are a form of luxurious escape which appeal to a special class, such presentations are appreciated only by those who have nothing else to do. You have given them a vacation from boredom, nothing more. Audiences who like this sort of thing have no energy, power, or inclination to advance your idea. Serious members of an audience seek those with real insights and programs. They do not waste their time or resources on triflers.